Presentations from Day 1 at Loughborough University Fine Art Department in this slide show.

[foogallery id=”1851″]

Following an introduction to Drawing / phenomenology: tracing lived experiences through drawing, by Conference Organiser and host Deborah Hartley, a diverse and insightful series of presentations covering intensely local to expansive global drawing projects ….

Deborah Harty: drawing is phenomenology?

Jane Cook: Drawing the Domestic: a practice-led phenomenological study through–drawing investigating notions of the experience of home.

Martin Lewis: Perfunctory Acts of Drawing.

Marion Arnold: The Sensing, Knowing Hand: a Phenomenological Drawing Tool.

Eleanor Morgan: Fixing the ephemeral: the materiality of sand-drawings.

Phil Sawdon: … feel my way … outline judgements … I made some pictures

…… there was a choice of 4 workshops for the afternoon session.

I selected the intriguingly titled : Gained in Translation: Drawing Art History presented by Sarah Jaffray from the Bridget Riley Foundation at The British Museum. Surprisingly this was a participatory session where we were encouraged to draw from the collection of British Museum prints inc great masters and more recent drawing works. Beginning with quick draw exercises to get us loosened up we worked through pictures at speed and then on to a longer 10 minute drawing session.  My selected drawing for this longer session was Michel Thevoz in the library of the Art Brut Museum, Graphite by Ariane Laroux. This longer focus on ‘copying’ or ‘Re, Representing’ a drawing enabled me to begin to understand the flow of the drawing through the artist’s eyes, by copying her drawing with intense attention to detail to honestly copy and represent her drawing.

My selected drawing for this longer session was Michel Thevoz in the library of the Art Brut Museum, Graphite by Ariane Laroux. This longer focus on ‘copying’ or ‘Re, Representing’ a drawing enabled me to begin to understand the flow of the drawing through the artist’s eyes, by copying her drawing with intense attention to detail to honestly copy and represent her drawing.

The drawing captured the subject, but left much of the subject out. Much of the paper remained white and untouched. Following the drawing from head to hand seemed to reveal decisions made by Ariane Laroux to draw her subject, which may have gone unnoticed without the attention to detail required to copy her drawing. This seemed to confirm the thesis that faithful copying from original art is valuable to the copier in terms of dexterity, skills and insight into the artistic process.

I was not attempting to make better the original, but to replicate it honestly to the best of one’s ability to make a genuine copy. I felt the process of drawing Ariane’s Drawing brought me closer to her process to draw her subject. It was no longer an exercise, but an engaged desire to be true to her drawing, and to be with her, in her mark making and her decisions to draw parts of her subject that illuminated her whole subject. I did not know or see her subject before her, as I did not know the Ruben’s or Leonardo’s subjects, but with licence and dedicated time to draw from her picture I got to know the subject and even closer to the artist’s representation of the subject. Whilst being drawn into the process and giving as much as I could into the timeframe I felt I wanted to talk to Ariane about her drawing choices, in this portrait, because I thought I ‘knew more’ than when I began.

Sarah Jaffray’s workshop focussed on translation, which is wholly pertinent, however I took from it ‘the right to copy’ as an educational, skills and insightful process of value. She, through the Bridget Riley Foundation, encourages drawings of the drawings, for the benefit of of the contemporary drawer.

This process encouraged me to question where Drawing and Phenomenology meet?

The workshop abstract :

Gained in Translation: Drawing Art History

Drawing from drawing is as old as the artist’s workshop: students drawing from their master’s work, tacked to the wall of a studio, began their journey to mastery through faithful copying. Today however, in the wake of post-modernism’s reaction against authority, copying from a ‘master’ feels outdated and has thus been erased from contemporary arts education.

For the past three years the Bridget Riley Art Foundation at the British Museum has worked with over 1,000 university art students to revive and interrogate the value of drawing from drawing as a contemporary research method. In the process of over 150 workshops we found that students who initially dismissed the practice as ‘servile copying’ began to legitimise the process with the language of translation.

Building on this qualitative research, our workshop will examine the practice of drawing from drawing through the lens of translation theory. We will discuss translation, in the manner of Walter Benjamin, as a mode of cognition that allows the translator to critically interrogate their own artistic language. Working through a series of drawing exercises from (reproductions of) drawings in the British Museum’s Prints and Drawings collection we will actively explore the question: what can translating teach the translator

Those interested in drawing from the collection can make an appointment at : www.britishmuseum.org.

The Artworks used from the British Museum collection:

1. Paul Cézanne, Study of a plaster Cupid, c.1890; graphite. 1935,0413.2

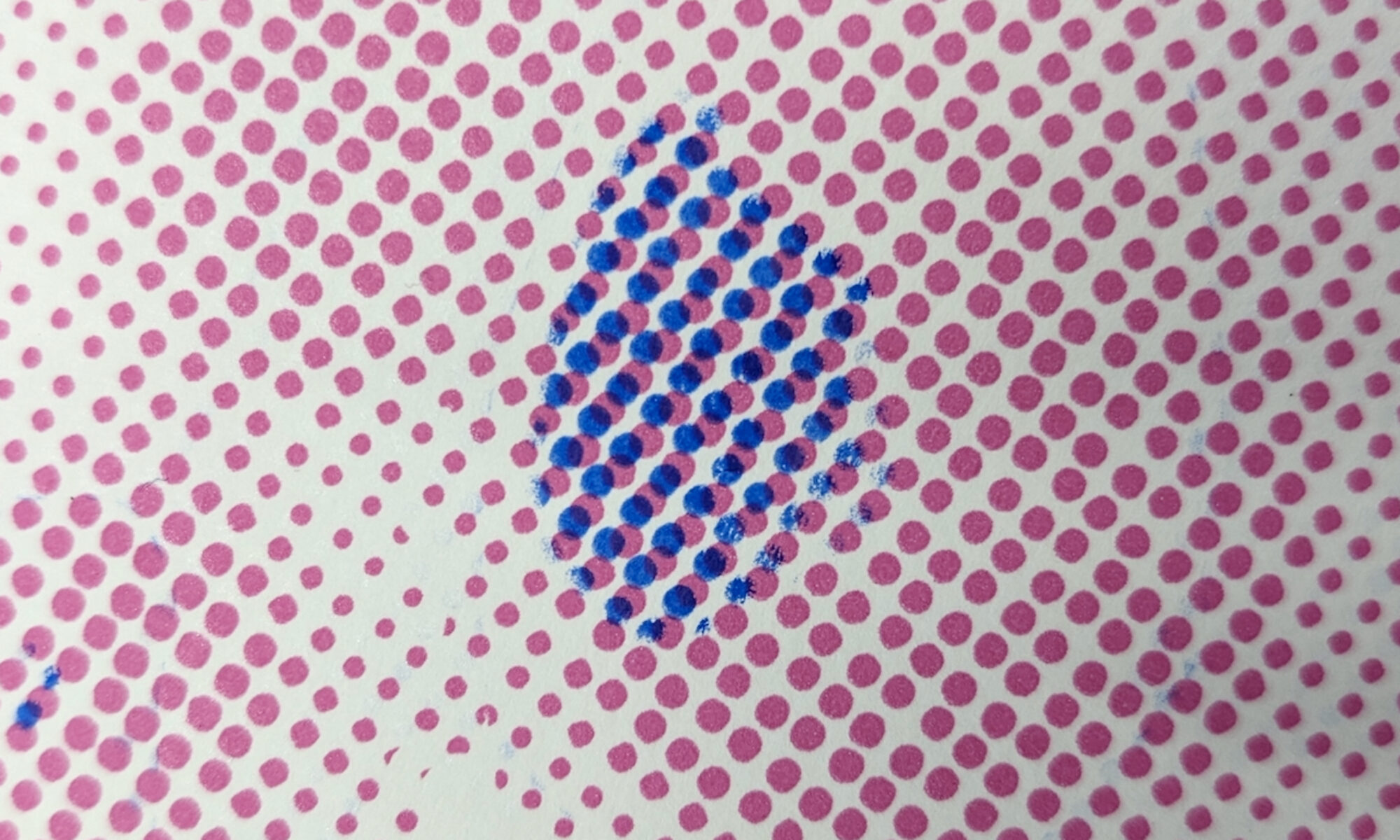

2. Bridget Riley, Untitled 2 (Circles with verticals), 1960; Pencil, blue ink and gouache paper. 2013,7097.2

3. Vincent van Gogh, La Crau from Montmajour, France, May 1888; Pen and brown ink, over black chalk and graphite. 1968,0210.20

4. Ariane Laroux, Michel Thevoz in the library of the Art Brut Museum; graphite. 2001,0929.12

5. Théodore Géricault, Study of Soldiers fighting Civilians, 1823; Graphite over red chalk. 1920,0216.3

6. Sol Lewitt, Untitled, 1971. Pen and yellow ink. 1981,1003.27

7. Antoine Watteau, Studies of a woman standing, seen from behind, a half-length woman with head in profile to left and women’s hands, 1684-1721; Red and black chalks, 1857,0228.213

8. Peter Paul Rubens, Mary Magdalene, c. 1620; Black chalk, heightened with white. 1912,1214.5; H16

9. Frank Auerbach, First drawing for ‘Ruth’, 1994; graphite. 2013,7059.48

10. Leonardo, The Virgin and Child, 1478-80; Pen and brown ink, over leadpoint, the lower sketch in leadpoint only. 1860,0616.100, P&P 100

11. Barbara Hepworth, Sculptural forms, c. 1938; ink on paper. 2008,7082.1

12. Honoré Daumier, Clown playing a drum, c.1865/7; Pen and black and grey ink, grey wash, watercolour, touches of gouache, and conté crayon, over black chalk underdrawing. 1968,0210.30