Photographic Portraiture In The Western Context

In the context of contemporary globalisation and social media imagery, the doctoral thesis resulting from the present research will address issues of portraiture from a diverse multicultural perspective, however the scope of the current report is limited to the Western tradition.

In a pre digital age Susan Sontag wrote: ‘Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation”. (Sontag,1977:135)This was an analogue environment where consumerist photography was in its populist infancy with photographic negatives posted to Kodak for processing and prints physically returned to the photographer for viewing and sharing. In the twenty-first century the instantaneity of digital camera technologies and channels of social media has produced a tsunami of images of human beings made and shared in an instant global environment. Participation, intrusion, ownership, collaboration, ethics between subjects and producers alike is even more complex than in the analogue 1970s. It is in this context that this research investigates questions of contemporary portraiture.

Discreet and Surreptitious Photography and Art

‘The camera is clumsy and crude. It meddles insolently in other people’saffairs. The lens scouts a crowd like the barrel of a gun.’(Barker, 2010:205)

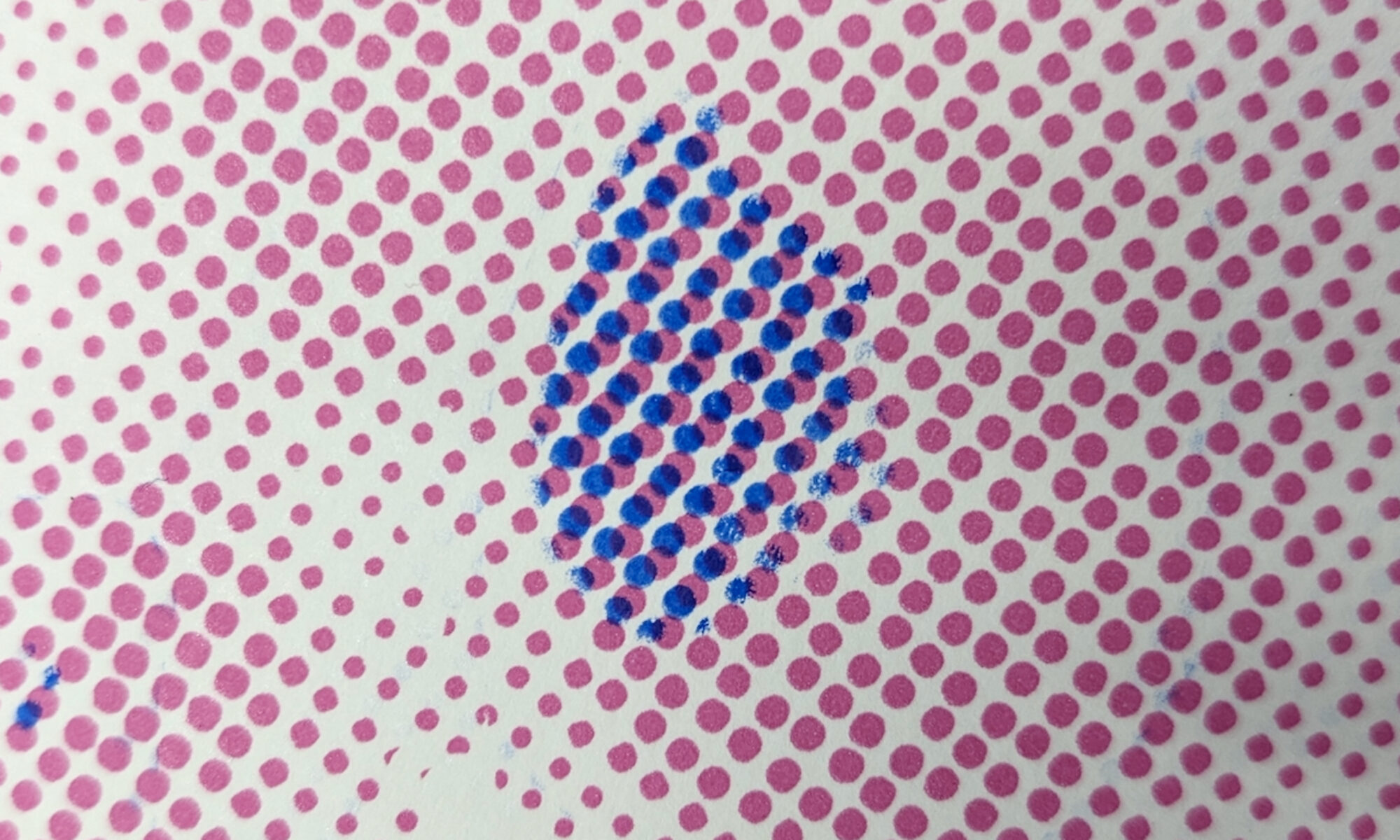

To build a portfolio of portrait images for subsequent drawn prints smart phone camera photography is the medium used in this research. In making these photographic references, surreptitious methods are adopted, to achieve a representative image of the subject, without them being aware of the lens and therefore ‘posing’, as indicated by Roland Barthes:

‘Once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of posing, I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image’.(Barthes, 2000:10)

Thissurreptitious practice could be perceived as a potentially fraudulent act and raises motivational and ethical questions.

The earliest Parisian street images were captured in 1838 by Daguerre and presented to King Ludwig 1 of Bavaria as proof of the invention of the daguerreotype. It has been argued that the practice of photography was inaugurated with a surreptitiously-made image where ‘a man having his boots polished … is hardly likely to have known that his picture was being in a very real sense, “taken”.’ (Barker, 2010:205)As image capturing technology matured in the early twentieth-century, photographers and artists consciously adopted and applied discreet and surreptitious photographic methods. In the spirit of enquiry, adventure and investigation, documentary photographers sought to expand the means of recording their subjects. In some cases deceptive means to hide their intentions from their subjects were adopted. An example is photographer Ilya Ehrenburg:

For many months I roamed Paris with a little camera. People would sometimes wonder why was I taking pictures of a fence or a road? They didn’t know that I was taking pictures of them … The Leica has a lateral viewfinder. It’s constructed like a periscope. I was photographing at 90°.(Barker, 2010:207)

Ehrenburg compares himself with a writer: ‘I can talk about this without laughing, a writer has his own notions of honesty. Our entire life is spent peeping into windows and listening at the keyhole – that’s our craft’. (ibid) Ehrenburg was an early adopter of voyeuristic photographic methods with many others following, including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Helen Levitt, Ben Shan, Paul Strand, Cartier Bresson, Brassai, Diane Arbus and Wickes Hine.

As technology and photographers developed their craft a variety of surreptitious methods of recording and ‘shooting’ were experimented with. It became easier to ‘take’ the subject by surprise when smaller cameras enabled street photography where no one at first expected it. It is reported that:

Early portable cameras were given a name: “detectives”. The design of the detective cameras was usually more fanciful than useful – one was designed as a stack of books, another a parcel; one fitted into a cane; another into an umbrella’s head or the heel of a man’s shoe. One camera was made like a revolver. (Phillips, 2010:13)

Quickly, public opinion went from tolerating the foibles of young and avid ‘kodakers’ to viewing these same men as unfairly and abusively ‘lying in wait to catch their prey. (ibid)

In the 1930s photographer, Walker Evans, made his rightly-famous social documentary work for the US Government’s Farm Security Administration.

He also adopted discreet techniques in his personal work:

Looking intrusively seems to have been Evans’ great pleasure,

and one of his most consistent interests. As he wrote to a friend:

Stare, it is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You’re not here long.’ (Garland-Thomson, 2009:118 as cited by McKay, 2013:339).

Later he invited friend and photographer Helen Levitt to accompany him to the subway, where he outfitted himself with a camera hidden under an overcoat, a cable release running from the camera on his chest down his sleeve to his hand. Evans wanted to photograph people without self-conscious projection, in private interior moments while on public transport. (ibid)

Contemporary artists have also adopted surreptitious image capture. Nan Goldin photographed from embedded participation in groups of subjects for familiarity and intimacy in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Heiferman, et al. 1986.)and Philip Lorca di-Corcia’s covert recording of Headswith elaborate hidden flashes in the street which: ‘offers unblinking insight into unguarded, distracted faces of total strangers, capturing moments of absolute, impenetrable introspection on to which we can only project our own assumptions.’ (MoMALearning, n.d.)

As well as ethical considerations, such surreptitious acts have legal implications. Di-Corcia was taken to the New York Supreme Court by one of his unsuspecting subjects. In his defence he pleaded his first amendment right to exhibit a photograph of the subject that had been taken without their knowledge. (Wortman,2010)US artist Barbara Kruger was sued for using a picture in It’s a Small World … Unless You Have to Clean It. A New York federal court judge ruled in Kruger’s favour, holding that, under state law and the First Amendment, the woman’s image was not used for purposes of trade, but rather in a work of art. (Gefter, 2006)

Beyond photography artists have made surreptitious recording core to their practice. In Vito Acconci’s Following Piece, the artist follows (stalks) random people in the streets and photographically documents the actions until they reach a private space. (Acconci,1969)In Sophie Calle’s Sleepersshe takes photographs of her nightly bed fellows. In Suite Vénitienne she follows a French man to a Venice hotel and secretly photographs his comings and goings. ‘She flirts with opposites: control and freedom, choice and compulsion, intimacy and distance. On one level, her art responds to the surfeit of choice in late capitalist society.’(Jeffries, 2009) She uses photography as a tool to document her artistic motivations to which she has commented: ‘Ultimately, my excitement was stronger than my hesitation.’(ibid)

In the age of social media a legal case centred on artist Richard Prince’s usage of images from the internet without consent and elicited comment: ‘Is Richard Prince a “trolling genius” or a plain old rip-off merchant?’(Gorton, et al 2015). New Portraitsfeatured thirty-eight images that Prince screen-grabbed from the ‘Suicide Girls’ Instagram channel, ink-jet printed onto large-scale canvases along with short social media comments, and a comment by the artist. Prince has used ‘Fair Use’ copyright law in the past, which rules that if you tweak something enough, it can become something original. So Prince, by adding his own, rather distasteful comments, enlarging the images and exhibiting them in a refined art context, will argue he has transformed them. One of the subjects of Prince’s New Portraits,Suicide Girls’ founder Missy Suicide, offered to sell her own prints for ninety dollars, with any proceeds going to charity. (ibid) She is taking control of her image and exerting her right to, and ownership, of her image.

Most recently artist, photographer writer Teju Cole published a collection of photographs and textsinspired by memories, fantasies, and introspections. This includes a photograph of a woman walking down a street from behind. On the facing page is the text:

I follow her for one city block. Thirty seconds after the first photograph, I take a second. Against my will, and oblivious to hers. I lose her to the crowd – the mutual danger is defused. On Instagram, the ones who see what you saw are called your followers. The word has a disquieting air. (Cole, 2017:295-6)

This brief summary of the use of surreptitious photography serves to establish the context for doctoral research into contemporary portraiture initiated from the smart phone photographic image and points to the complex ethical considerations that the research addresses.

Bibliography/Reference List.

Acconci, V.1969. Following Piece.Available at: http://www.vitoacconci.org/portfolio_page/following-piece-1969/

[accessed 13thSeptember 2019]

Alcoff, L,M. 1991. The Problem of Speaking for Others.Cultural Critique No 20. USA. University of Minnesota.

Angier, R. 2015. Train your Gaze: A practical and Theoretical Introduction to Portrait Photography. London. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Barker,S. 2010.Up Periscope! Photography and the Surrepcious Image.In: Phipps,S. Exposed. Voyeurism, surveillance, and the camera since 1870.USA. San Francisco Museum of Modern art in association with Yale University Press.

Barthes, R. 2000. Camera Lucida.1980. Trans. Richard Howard. London, Vintage.

Barnes, J.1982.Aristotle.Oxford University Press

Bacon,F.Use of Photography. Available at: http://francis-bacon.com/life/family-friends-sitters[Last visited August 2019]

BBC editorial guidelines. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidance/consent/how) [accessed 5thSeptember 2019]

Benjamin, W. 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. UK. Penguin.

Benson, R. 2008. The Printed Picture. USA. The Museum of Modern Art New York.

Berger, J. Savage, J. 2005. Berger on drawing. Cork. Occasional press.

Berger, J. 2013. Understanding a photograph. UK. Penguin.

Booth-Clibborn, 2001.I am a Camera. London. Saatchi Gallery.

Brassaï. 1976. The Secret Paris of the 30’s. New York. Pantheon Books.

Brilliant, R.1991. Portraiture.London. Reaktion.

Büttner,A. 2016. Beggars and iPhones. CatalogueKunsthalle Vienna Austria.

Cain, P.2010. Drawing: The Enactive Evolution of the Practitioner. Bristol. Intellect Books.

Chilisa, B. (2012) Indigenous research methodologies. USA. Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage.

Close,C. interviews Vija Celmins Artspace. Available at: https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/book_report/chuck-close-in-conversation-with-vija-celmins-about-her-dense-yet-infinite-drawings-54732

[Accessed September 2019]

Cole, T. 2017. Blind Spot.London. Faber& Faber.

Cubitt, S. 2014. The Practice of Light: A Genealogy of Visual Technologies from Prints to Pixels. Cambridge, MA, USA.MIT Press.

Cumming, L. 2009. A Face to the World: On Self-portraits. UK. HarperCollins.

Craig-Martin, Michael. 1995. Drawing the Line: Reappraising Drawing, Past and Present.Southampton Art Gallery;London.The South Bank Centre.

Coppel, S. Daunt, C.Tallman, S. Fischer, H., Seligman, I. and Ramkalawon, J. 2017. The American Dream: Pop to the Present. London. British Museum.

Cue, E. 2016. Interview With Jenny Saville.Huffington Post, 6thAugust.Available at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/interview-with-jenny-savi_b_10324460?guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly9kdWNrZHVja2dvLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAACqP4PI4Nj3grnlJ89mSvcuAwU3cveoP2imireEpomsUdC529TURQVpMzmeCFfTuFSRmy9c3DG2KdBuJHoslB13cxf_O6SXRlnoY5QRpiI5tH8EwO-KUU6fhGSeQFS3FESy_mabJw4zElV-Yu1WWwLIOWamUGPDDudpfCt975cxg&guccounter=2

[accessed 5th September 2019].

Dautruche, B.K. Why Positionality & Intersectionality are Important Concepts forRhetoric.My Most Humble opinion. Available at: https://bkdautru.expressions.syr.edu

[accessed 19 September 2019]

Davidson, B. Braithwaite, F. and Geldzahler, H. 2011. Subway. New York. Steidl.

Di-Corcia, PL. Heads.Available at: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/philip-lorca-dicorcia-head-10-2002/[accessed 19 September 2019]

Di Pippo, A.F. 2000. The Concept of Poiesis in Heidegger’s An Introduction to Metaphysics. Thinking fundamentals. Vienna. IVM.

Downs, S. Tormey, J. Selby, A. Sawdon, P. 2007. Drawing Now: Between the Lines of Contemporary art. London. IB Tauris.

Dyson, A. 2009. Printmakers’ Secrets. A&C Black. London

The Economist. 2015. Phono SapiensLondon. Available at:https://www.economist.com/leaders/2015/02/26/planet-of-the-phones[accessed September 20th2019]

Eggum, A.1989. Munch and Photography. London.Yale University Press.

Eichenberg, Fritz. 1976. The Art of the Print: Masterpieces, hHstory, Techniques. London. Thames and Hudson.

Feaver, W. 2002. Lucian Freud. London. Tate Publishing.

Feldman, Frayda; Schellmann, Jörg. 1988. Andy Warhol Prints: a catalogue raisonné. New York.

Fleming,S. 2013. Social research in sport (and beyond): Notes on exceptions to informed consent. UK. Research Ethics Sage.

Ford, C. A Pre-Raphaelite Partnership: Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Robert Parsons. London. Burlington Magazine. May 2004. No. 1214 – Vol 146.

Fried, M. 2008. Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before. USA. Yale University Press.

Garland-Thomson, R. 2009. Staring: How We Look.New York: Oxford University Press.Cited: McKay,C. 2013. ‘Covert: the artist as Voyeur’. Sydney. Surveillance and Society.

Garner, S. ed. 2012. Writing on Drawing: Essays on Drawing Practice and Research. Bristol. Intellect Books.

Gefter, P. 2006. Street photography a right or invasion.NY Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/17/arts/street-photography-a-right-or-invasion.[accessed 19 September

Gilden, B. 2015. Face.Stockport. Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Graham-Dixon, A. Howgate, S. Nairne, S. and Higgins, J. 2013. 21st-century Portraits. London. National Portrait Gallery.

Greenwood, W. 2019. Central Islamic Lands at the Museum of Art in Doha.The New Arab. Available at: https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/society/2016/7/26/images-and-idols-the-figurative-in-islamic-art

[accessed 9th September 2019].

Griffiths, P.J.1971. Vietnam Inc. NYC. Collier books.

Goffman, E. (1971). The Presenation of Self in Everyday Life.London. Penquin.

Gorton,T; Allwood, E.H; Taylor, T. 2015.Is it really OK to sell other people’s Instagrams as Art? Dazed.https://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/24887/1/is-it-really-ok-to-sell-other-peoples-instagrams-as-art[accessed 13thSeptember 2019]

Hammer, M. 2007. The Naked Portrait.Edinburgh. National Gallery of Scotland.

Harris, J. 2008.Identity Theft: Cultural Colonization and Contemporary art.Liverpool University Press

Harty.D. 2018. Drawing is Phenomenology.Leicester. De Montfort University.

Heiferman,M; Holborn, M; Fletcher, S. 1986. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.New York. Aperture.

Hill, J.E. 2011. Engaged Observers: Documentary Photography Since the Sixties: Brett Abbott.USA. J. Paul Getty Museum.

Hockney, D. 2001. Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. London. Thames and Hudson.

Hoskins, S. 2001. Water-based Screenprinting.London. A. & C. Black.

Hustvedt, S. 2016. A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex, and the Mind. New York. Simon and Schuster .

Hyde, L. 2006. The gift: Creativity and the artist in the modern world. Edinburgh. Cannogate.

Inwood, M.1993.Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 1770-1831; 1944-; Bosanquet, Bernard; Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 1770-1831. London. Penguin.

Jeffries,S. 2009. Sophie Calle. Stalker, Stripper, Sleeper, Spy.London Guardian [accessed13thSeptember 2019]

Jolly, M. 2006. Faces of the Living Dead: the Belief in Spirit Photography. London.

British Library.

Kara, H. 2018. Research Ethics, in the Real World. Bristol.PolicyPress.

Katz, J.S. Gross, L.P. and Ruby, J. eds. 1988. Image Ethics: The Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Film, and Television. Oxford University Press

Keller, J. 1993. Walker Evans and Many Are Called:Shooting blind. History of Photography, 17:2, 152-165, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.1993.10442613

King, E.A. and Levin, G. 2010. Ethics and the Visual Arts. New York. Simon and Schuster.

Kholeif, Omar. 2015.You are Here: Art After the Internet.Manchester. Cornerhouse/SPACE.

Kovats, T. Darwent, C. MacFarlane, K. and Stout, K. 2005. The Drawing Book. A Survey of Drawing: The Primary Means of Expression. London. Black Dog Publishing.

Kruszynski, A, Bezzola, T, Lingwood, J. Thomas Struth Photographs 1978 -2010. New York. Monacelli Press.

Lambert, L. (2014) Research for indigenous survival: Indigenous research methodologies in behavioural sciences. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Levi-Strauss, C. Conflict exists: p58-60. Cited: Hyde, L. 2006. The gift: Creativity and the artist in the modern world. Edinburgh. Cannogate.

Liamputtong, P. 2010. Performing qualitative cross-cultural research. UK. Cambridge University Press.

Luft, S. and Overgaard, S. 2013. The Routledge Companion to Phenomenology. London. Routledge.

Malbert, R. 2015. Drawing People: the Human Figure in Contemporary Art. London. Thames & Hudson.

Maslen, M. and Southern, J. 2014. Drawing Projects: An Exploration of the Language of Drawing. London. Black Dog Publishing.

Matthews, P.M. 2013. The Significance of Beauty: Kant on Feeling and the System of the Mind (Vol. 44). Germany. Springer Science & Business Media.

McCausland, E. 1937. Kathe kollwitz – Portrait of the Artist printmaker.Birmingham. IKON and British Museum Catalogue.

McFee,G, 2010.Ethics, knowledge and truth in sports research: an epistemology of sport.London New York.Routledge.

McKay,C. 2013. ‘Covert: the artist as Voyeur’. Sydney. Surveillance and Society.

Modern, T. W.A. Baker, S. and Phillips, S.S. 2010. Exposed: voyeurism, surveillance, and the camera. USA. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Tate Publ.

MoMALearning. Available at: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/philip-lorca-dicorcia-head-10-2002/[Accessed September 20th2019)

Morton, M. 2017. Max Klinger and Wilhelmine Culture: On the Threshold of German Modernism. London. Routledge.

Moustakas, C.1994.Phenomenological Research Methods.New York.

Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Moustakas, C.1977. Creative Life.USA.Sage.

Mullins, C. 2015. Picturing People: the New State of the Art. London. Thames & Hudson.

Newhall, B. 1964. The History of Photography; from 1839 to the Present Day. New York. Penumbra Foundation.

Pallasmaa, J. 2009. The thinking hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture.UK Chichester. John Willey.

Parry, J.D. ed. 2010. Art and phenomenology. London. Routledge.

Plato Stanford Encyclopedia. Available at: (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-internet-research/#InfCon[accessed September 12th 2019]

Pelzer-Montada, R. 2018. Perspectives on Contemporary Printmaking. UK.Manchester University Press

Pergam, E.A. 2015. Drawing in the Twenty-first Century: The Politics and Poetics of Contemporary Practice. UK. Ashgate.

Petherbridge, D. 2010. The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice. USA. Yale University Press.

Phipps,S. Exposed. Voyeurism, surveillance, and the camera since 1870.USA. San Francisco Museum of Modern art in association with Yale University Press.

Potts, K and Brown, L. 2015. Research as Resistance: revisiting critical, Indigenous, and anti oppressive approaches.Toronto: Canada.

Prelinger, E. Kollwitz, K. Comini, A. and Bachert, H. 1992. Käthe Kollwitz: National Gallery of Art, Washington;[catalog of an exhibition held May 3-August 16]. USA. Yale University Press.

Price, M. ed. 2013. Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing. London. Phaidon Press Limited.

Printmaking techniques : The Vasari Corridor & its Self-Portrait Collection. https://www.handprinted.co.uk/[Last visited August 2019]

Ruskin, J. 2012. The Elements of Drawing. Courier Corporation.

Schama, S. and van Rijn, R.H. 1999. Rembrandt’s Eyes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Serge, G. 1985 How New York stole the idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War. USA. University of Chicago Press

Sherwood,J. (2013) An Aborigina health worker’s research story. In Mertens, D., Cram, F and Chilisa, B. (eds) Indigenous pathways into social research: voices of a new generation, 203-17. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Simmons, L. 2010. “Drawing has Always been more than Drawing”:Derrida and disegno. Interstices: Journal of Architecture and Related Arts. Aukland New Zealand.

Smith, C. 2012. Decolonising methodologies. London. Zed Books.

Sontag, S. 1977.On Photography.McMillan. New York.

Wortman,R. 2010. Available at: http://www.gnovisjournal.org/2010/04/25/street-level-intersections-art-and-law-philip-lorca-dicorcias-heads-project-and-nussenzweig/[accessed September 2019]

Sontag, S.1987.Against Interpretation and Other Essays.London. Deutsch.

Soussloff, C.M. 2006. The Subject in Art: Portraiture and the Birth of the Modern. USA. Duke University Press.

Spivak, G.C. and Harasym, S., 2014. The post-colonial critic: Interviews, strategies, dialogues. London. Routledge.

Stewart, J. Watkins, J. 2017. Thomas Bock.Birmingham.IKON and Cornerhouse

Thompson, D.V. 1933. The Craftsman’s Handbook: Il Libro dell’ArteCennino d’Andrea Cennini. USA. New Flaven.

Trodd,T. 2011. Screen/space: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art. Manchester University Press.

Van Kruiselbergen, A. 2013. Breakfast with LucianGeordie Greig. Farrar, Straus and Giroux New York. Random House.

Varnedoe,K. 2002. Chuck Close. Blood Sweat and Tears.New York. Pace Wildenstein

Vija Celmins video interview : Painting Takes Just a Second to Go In. London.Tate Shorts. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsbkzSrCdIg

[Accessed September 2019]

Walter, M. and Anderson, C (2016) Indigenous Statistics: a quantitative research methodology. Abingdon. Routledge.

West, S. 2000. The Visual Arts in Germany 1890-1937: Utopia and Despair. UK. Manchester University Press.

Wilde, O. 2003. The Picture of Dorian Gray. London. Penguin.

Wilson, S. (2008) Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods.Halifax and Winnepeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Woodall, J. ed. 1997. Portraiture: Facing the Subject. UK. Manchester University Press.

Worley, L. 2011. The Poiesis of Human Nature’: an Exploration of the Concept of an Ethical Self. Australia. Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University.

Zöllner, F. 2000. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519. GmbH. Taschen.