Thomas Bock Ikon gallery December 2017

Today in Birmingham’s ikon gallery saw the long in the curating first exhibition outside Australia dedicated to the work of Thomas Bock (c 1793 – 1855). As ikon director Jonathan Watkins and Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery director, Janet Carding say in their forward to the beautifully and insightfully illustrated catalogue ; ‘It comprises a selection of drawings, paintings and photographs that demonstrate not only the artist’s technical skill, but also sensitivity to a wide range of subject matter including portraits of Tasmanian Aborigines, his fellow criminals as well as free settlers in Hobart Town, nudes, landscapes and every day scenes, occasionally giving touching inside into his domestic life.

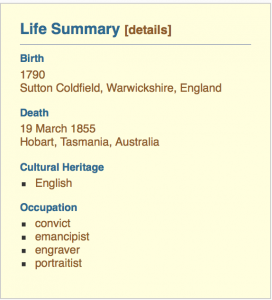

Bock was one of the most important artists working in Australia during the colonial years. Born in Birmingham, trained there as an engraver and miniature painter, in 1823 he was found guilty of ’administering concoctions for certain herbs …… with the intent to cause miscarriage’ and sentenced to transportation for fourteen years. He arrived in Hobart the following year where quickly he was pressed into service is a convict artist, engraving banknotes, illustrations for a local almanac and commercial stationery. An early commission was a number of portraits of captured bushrangers, before and after execution by hanging, including the notorious cannibal Alexander Pearce.

In a short space of time, Bock’s life was turned upside down. Once a respectable artisan in his early 20s, with a good address in a booming industrial town, he now found himself at the edge of the known world in the company of compatriots who were as desperate as they were depraved. There are no surviving diaries that document his personal journey, but Bock’s artistic output on arrival, through conditional absolute pardon and until his death – marked by an obituary but described him as artist of a very high order – is a rich seam of observation that was at once subtle and astonishing.

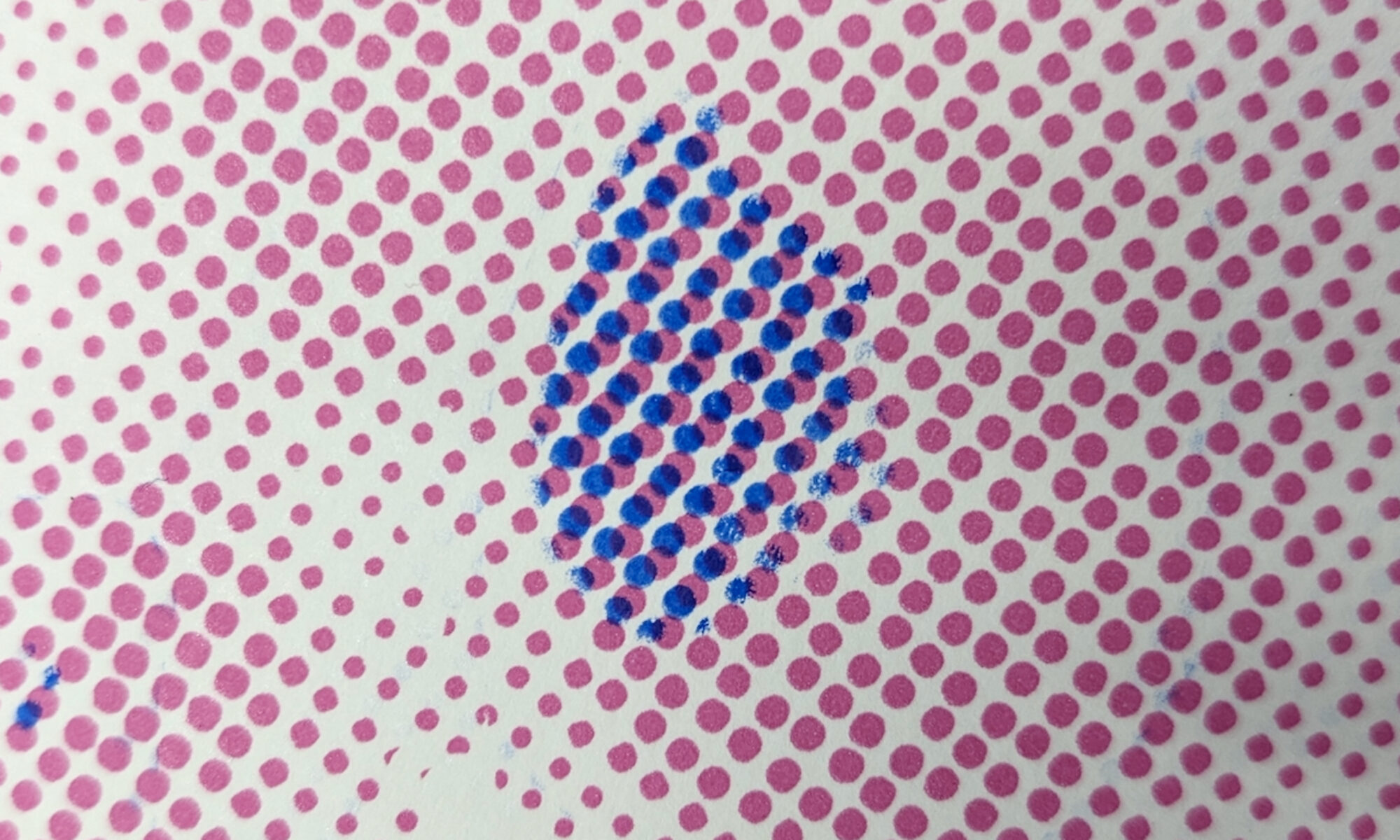

Most significant in this respect is a box series of portraits of Tasmanian Aborigines, commissioned by George Augustus Robinson during 1831-35, now in the British Museum. It is a master set, from which a number of copies were made. The drawing throughout is very fine and the likenesses probably very true, and having them at the heart of this exhibition will effectively convey the tragedies suffered by Indigenous people through the British colonisation of Australia. The sitters – including Trukanini (c1812-76) have a demeanour that conveys both pride and despair. For British audiences on the whole this work will be a revelation; for Aboriginal visitors to the exhibition in Hobart – who know the sad narrative only too well – it will be a rare and poignant opportunity to see firsthand such early pictures of their ancestors.

The exhibition and history reflects a literally amazing story of a Birmingham born trained artist and convicted criminal who sketched his passage from Woolwich in July 1823 to Tasmania in January 1824. The sketches begin with a family, and a view of the city, both probably his own. They follow the English, Cape Verde and South Africa coastlines as he reaches Hobart and is immediately put to work for the Bank of Van Dieman’s Land engraving notes.

The exhibition and the walking talk by Jane Stewart of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and Tasmanian Artist, writer and historian Julie Gough took us through the works on the wall. Jane explained the depth of history, skills and talents of Thomas Bock and concluded at a glazed box holding the portrait of a young Tasmanian woman ‘taken in’, from Flinders Island of incarceration, by a British serving family in Hobart to be ‘civilised’. The Franklins commissioned Bock to paint a portrait of Mithina (Mathinna) in the red dress. There is much history to this image which Jane and Julia shared with us, including the fact that the original painting was framed by an oval mount which removed Mathinna’s feet from view. On purpose we do not not know, but the portrait is now exhibited in a frame showing her whole body.

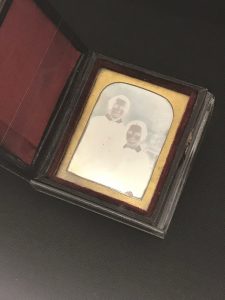

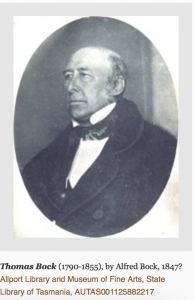

Director Watkins also introduced another glazed case by lifting the leather cover to reveal 3 daguerreotypes taken by Bock only three years after the process was invented in France. It is claimed that Thomas Bock was the first person to introduce the technique to Tasmania. He passed on his photographic business to his step son Alfred who in turn introduced the Carte de Visite to Hobart. The exhibition does not include an image of Thomas Bock, and one is extremely hard to locate, perhaps. because of Bock’s very real criminal history in Britain. However the Australian Dictionary of Biography holds a photograph by Alfred, along with his Biography which I include here as I ‘missed’ seeing him alongside the images he created.

Finally Julia walked us round the gallery to furnish us with the historical context to Bock’s artworks. She was aided by, appropriately enough, a miniature projector with her slide show being projected on the wall spaces between the frames. Director Watkins showed a steady and stable hand to keep the beam straight and true. Much like the exhibition as a whole that delivers revelations about a little known, until now, Birmingham, British artist and his role in reflecting the Indigenous peoples of Tasamania.

[foogallery id=”2532″]

Slide Show

The exhibition is on until March next year and there are a range of talks this week culminating in a symposium on Friday 15th:

Menzies Centre for Australian Studies & Ikon

Thomas Bock Symposium Convicts, Race, and Art

This one-day symposium is a collaboration between King’s College London and Ikon.

Bock was one of the most important artists working in Australia during the colonial years. He trained as an engraver and miniature painter in Birmingham before, in 1823, being found guilty of “administering concoctions of certain herbs … with the intent to cause miscarriage”, for which his sentence was transportation for fourteen years. Bock arrived in Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land (present-day Tasmania, Australia) the following year, where he was quickly pressed into service as a convict artist, engraving bank notes, illustrations for a local almanac, cheques, commercial stationery and so on. An early commission was a number of portraits of captured bushrangers, before and after execution by hanging, including the notorious cannibal Alexander Pearce. Bock’s portraits of Aboriginal Tasmanians are some of the most important in Australian art, including that featured here of Mathinna, daughter of Towterer and his wife Wongerneep of the Lowreenne people.

Experts will contextualise Bock’s life and work, while engaging in debates about ‘art in a time of colony’, the representation of Australia’s Indigenous peoples, and the politics and experience of transportation from the Midlands to colonial Australia.

Programme

10:00-10:30 Registration, Anatomy Museum, Level 6, King’s Building

10:30-1045 Welcome by Dr Ian Henderson, Director MCAS

10:45-12:30 Industrial Birmingham to Colonial Van Diemen’s Land

Dr Malcolm Dick, University of Birmingham

Thomas Bock’s Birmingham: Industry and Culture in “the city of a thousand trades”

Professor Judith A. Allen, Indiana University Bloomington

Thomas Bock’s conviction: Men, and the rise and fall of the new capital crime of abortion, 1803-37

Dr David Meredith, University of Oxford

On the transportation system and Van Diemen’s Land

12:30-13:30 Lunch

13:30-15:00 Convicts, Art, and Knowledge

Professor Clare Anderson, University of Leicester

Convicts and Penal Colonies in 19th-Century Science and Collecting: A Global Perspective

Professor Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, University of Birmingham

Thomas Bock and Edmund Clark: Savagery and Redemption in Ikon’s criminal portraiture, colonial and contemporary

Dr Ian Henderson, Menzies Centre King’s College London

Green Arcades Project: Art and Sociability in Nineteenth-Century Hobart Town

15:00-15:30 Afternoon Tea

15:30-17:00 Bock and the Tasmanians

Jane Stewart, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

On Bock and the history of art in Tasmania

Dr Gaye Sculthorpe, British Museum

Thomas Bock and the mystery of Trukanini’s necklace

Dr Julie Gough, Artist

The race of representation: What the works by Bock and his colonial contemporaries offer on the circumstances of Tasmanian Aboriginal people

17:30-19:30 Reception for Ikon’s Thomas Bock Exhibition

18:00 Jonathan Watkins, Director, Ikon Gallery on the exhibition

Image: Thomas Thomas Bock Mithina (Mathinna) (1842) Watercolour Presented by J H Clark 1951, AG290

Courtesy Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

.

My selected drawing for this longer session was

My selected drawing for this longer session was