Photography and Lived Experience

Symposium in June at University of Huddersfield,

School of Art, Design and Architecture.

Name: Jonnie Turpie

Contact details: Edward.turpie@mail.bcu.ac.uk Birmingham School of Art, Birmingham City University. Mob: 07748766824

Research site: printsanew.jonnieturpie.com

Consenting Adults – Portraiture and Discreet Photography

Introduction

My practice led research: Contemporary Portraiture: smart phone, drawing and printmaking began by mapping out the triangulation between the three media. These relationships would govern the artistic portrait interpretations at the centre of the research. One motivation was feelings of a lack of respect afforded to filmed subjects in the production of factual television. Having had a TV industry career I had experienced the drive of the narrative to ‘edit down’ hard found and recorded interviews, with trusting subjects to fit the particular thrust of a linear argument. This was under the subject’s signed consent to their contribution being used for a particular programme as per legal standards. (BBC editorial guidelines)(1)

Singular, drawn and printed portraits were to address this by attempting to reflect a selected subject honestly and with respect. But the premise of the practice to achieve this goal was to begin with a discreet smart phone photograph, made in close proximity to subjects, who are not aware of their participation. Although subjects, at this stage of the research maybe known to the artist, this surreptitious practice could be perceived as a potentially fraudulent act.

The research ethical statement established the ground rules of planned engagements. One clear parameter was that children would not be subjects of portraits. The developing research methodology makes offers to subjects to consent to their participation retrospectively, when sharing of a final portrait is made between artist and subject. This is an intense lived experience where the personas of both are made real, which the researcher captures, while the subject ‘takes’ their portrait into their life.

It draws upon a Heuristic research model whichaccording to Douglass & Moustakas:‘requires a subjective process of reflecting, exploring, sifting, and elucidating the nature of the phenomenon under investigation (Douglass & Moustakas, 1985, p.40. in Hiles. D)(2)

This paper will outline the lived experience of photographic and artistic practice from the researcher’s perspective and that of the unknowing subject as they come face to face across the portrait.

Consenting Adults

When considering this call I was researching the use of photography made by turn of the century artists including the Subject in Art in Austro Hungarian philosophical and psychological transformations (by C.M. Soussloff, 2006)(3), and the parallel development of art in northern Europe. Are Eggum, A.1989) (4) At this time photography was no longer a novelty and was accessible in these societies. Visual artists had ‘got over the threat’ to their professions and were applying photographic and pictorial techniques in their artefacts. The pre-eminent artist Edvard Munch was unapologetic about the use of photography to support his painting. He would take and request photographs from his subjects to aid his memory. Rather than decry the new medium he embraced it to aid his memory of subjects he made visual in his ‘mind’s eye’. His art is his interpretation of his subjects, many of which are based on recollection, the psychological theory, differentiating interior, from outer physical reality. As Ola Hansson notes: ‘Munch did not paint pictures of nature, but subjective ‘pictures of recollection, pictures that have burnt or etched their images in his mind.’ (Ola Hansson. Ibid p133)

100 years on, photography has become accessible to all through digital technologies, cameras and software. This research takes account and pays respect to the century of immense photographic practice, adoption and application in documentary, journalistic and artistic genres, while investigating the implications of the ubiquitousness of the smart phone, which according to the Economist is ‘a ‘natural’ item of 21st century human apparel. (It has even been said) we are now ‘Phono Sapiens’ (Economist 2015) (5).

The journey to the drawn and printed portrait via smart phone discreet photography raises questions of voyeurism, documentary photography and artistic interpretation. Carolyn McKay is an artist using discreet media techniques to initiate her art works. She tussles with the ethics of recording subjects without their knowledge and consent, and refers to Susan Sontag. (7) (McKay.C,2013)

‘’To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see them selves, by having knowledge of them they can never have.’ [. . . ] ‘there is something on people’s faces when they don’t know they are being observed that never appears when they do . . . their expressions are private ones, not those they would offer to the camera.’

Although tussling with ethical considerations McKay counters by referring to Walker Evans who covertly photographed New York subway passengers with his 35 mm camera hidden under his coat and said: ‘Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long (Garland-Thompson. 2009)

Before presenting the intracies of lived experience and consent in portrait making, the issue of the rights, or not, of the artist to embark upon the portrait process should be addressed. In early pursuits of ‘capturing’ images of people, photographers assumed the right to document and make records of subjects to be distributed beyond their social and cultural environment. The status of the photographer was not called into question. Many were sanctioned by Imperialist societies to make colonial missions into native communities and similarly western working class communities, in the name of expanding anthropological knowledge. And also in pursuit of making progressive social change as in Evan’s and Dorthea Lange’s FSA US Depression photography.

In the global transmedia environment photographic portrait methodologies and considerations have to be made: the understanding that ‘Soul theft’ is a reality for those whose images are ‘taken’ against their will; The Gaze and the assumed right to look from (male)(white) (middle class) perspectives; the Positionality of the maker in relation to the subject; Faiths and beliefs that challenge the right to represent the human image. Post feminist and colonial philosophy has enabled questioning of the representation of the other and that of the purveyor of the images. These considerations are forming the theoretical framework of this research.

Portraiture

The intention of this Practice-Led research is to create portraits that make material and tangible the interpretation of the subject, through visualising what was in the artist’s ‘mind’s eye’ when meeting and selecting a subject. The initial artistic decisions are made in the ‘lived-in’ world with a smart phone in hand. Always discreet. Why ‘discreet’? Because as we have understood from Sontag and others,people act differently when they do not know they are under the camera’s gaze. Their image is free from conscious presentation, making direct eye contact with the camera, photographer and subsequent viewer.

This lived experience is a phenomenological event where, the camera/phone becomes the artist’s gaze in real time, in the world. Even when eyes are diverted from the subject both artist and subject are in proximity as beings, the camera allows the view of the subject to be maintained. A visual connection is provided through the technology of the camera that allows the artist to stay connected with the subject despite averting their eyes from them, and thereby becoming a receptacle for the interpretation.

From smart phone to the drawn image.

The act of drawing enables the subject to be reflected upon, as is the motivation to represent them. This is a further lived experience with many material and aesthetic decisions in play. Penciling, chalking, crayoning, scratching, erasing, background creation, are all experiences of reflection and interpretation. As is being alone with the image in the studio: tinkering, elaborating, worrying, embellishing, leaving and returning to review the representation of the subject, before acceptance is reached.

The final printmaking phase.

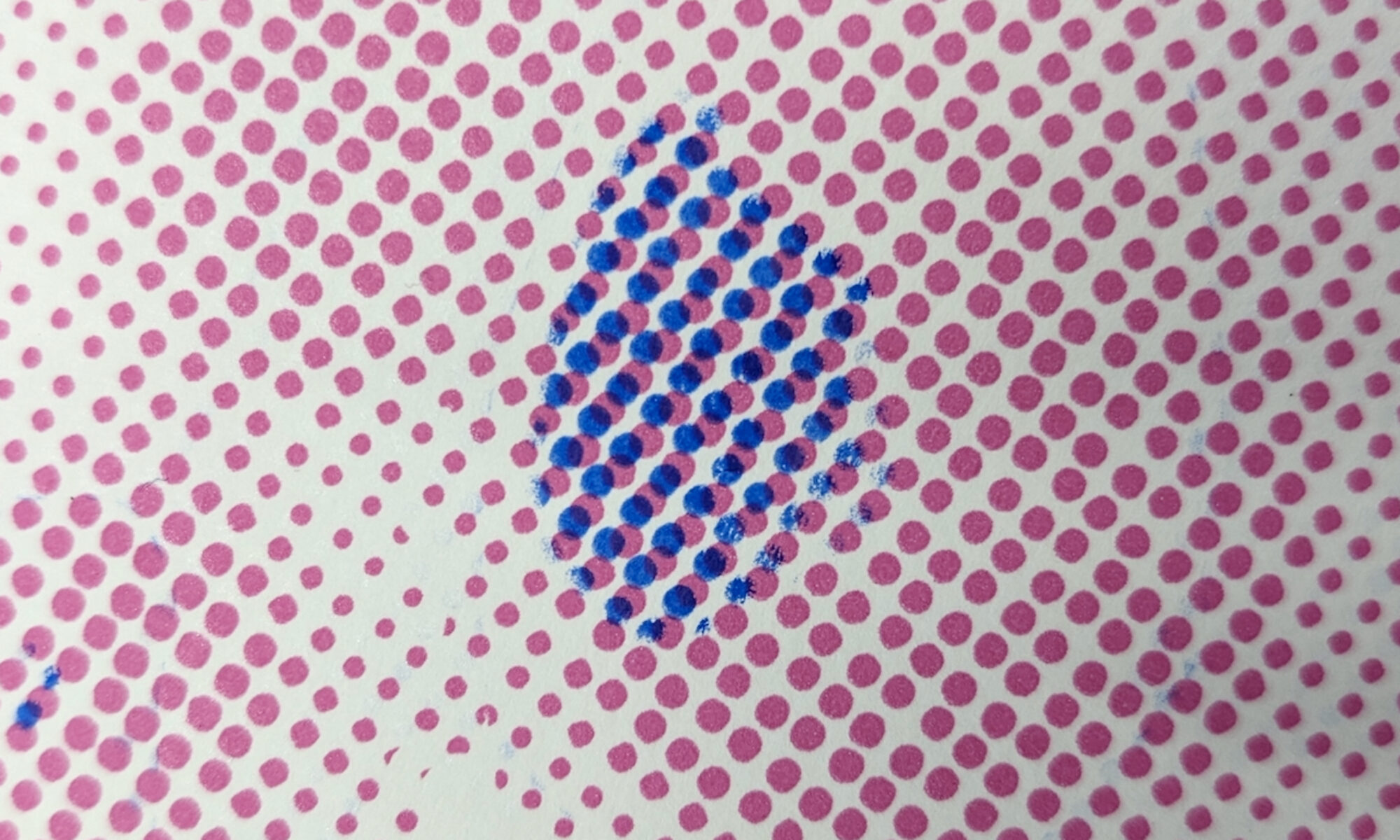

The process continues with the drawn image being exposed on to a silk screen in preparation for printing. Another creative lived experience. The inks, paper, pressures, scale, colours, unplanned chance process occurrences all keep the artist’s attention fully focused. Finally a large-scale portrait will grace the print room tables to be viewed and assessed. The artist is full of anticipation of whether the final portrait has fulfilled the aspirations held on the initial taking of the small smart phone image, from the subject.

CONSENT and SHARING

A completed portrait brings the opportunity to share in the wider world. The artist can make the portrait public by submitting for exhibition and reap responses from viewing audiences. However the subject is unaware of their portrait and has not given their consent to be portrayed. In the arts this could be laid to one side as the artefact is the work of the artist and that is paramount. In doctoral research terms consent is required. In moral and ethical terms consent is a necessity.

To achieve consent a sharing of the portrait with its subject is necessary. This could and has been successfully applied through making email, text and personal contact with subjects to inform them that a portrait has been made. This is the beginning of a new, shared lived experience between artist and subject. The planned but enigmatic encounter is loaded with anticipation for both parties. It is an intense experience where the personas of both are made real, which the researcher captures, while the subject ‘takes’ the experience of portrayal by another, into their lived experience. In addition the subject literally takes their portrait into their life as the artist offers them the first edition of the finished portrait.

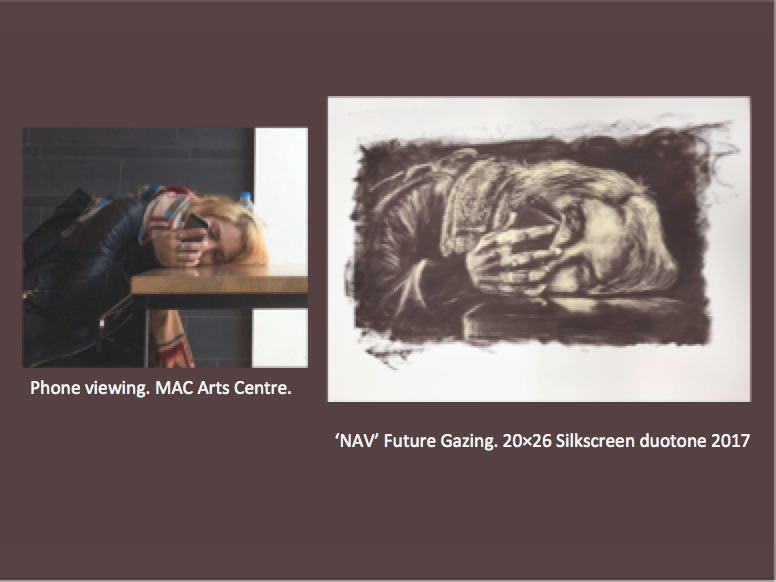

Although a heightened encounter the process of sharing can be relatively straightforward when the artist and subject are known to each other. When they are not, a period of investigation can bring both parties together. In this situation the encounter is further intensified, at least on the artist’s side. (slide Nav photo and print) A documented trail of exchanges between artist and subject is an acknowledgement of the subject’s participation. Affirmative words of acceptance of the portrait are testament to consent and a positive shared lived experience

(slide sharing page)i

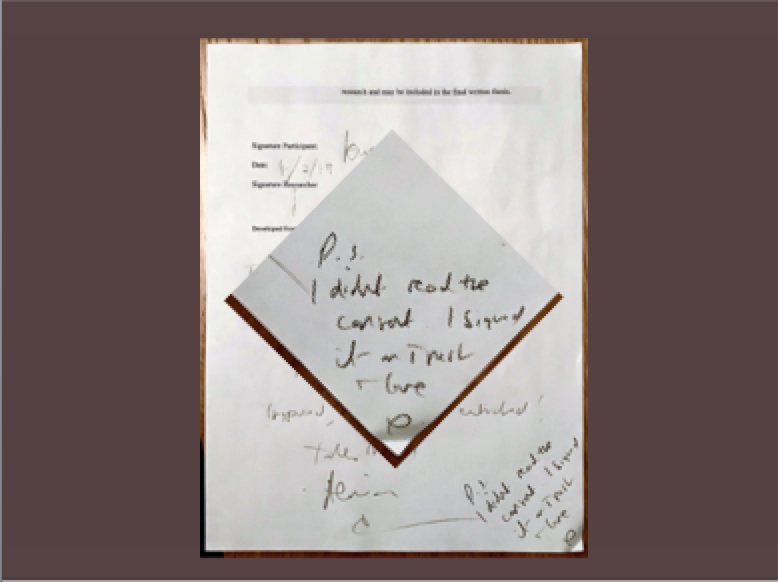

Anecdotal evidence is acceptable to both parties, but it is not legitimate proof of permission. It may be a trusted mutual understanding, but it is not a formal agreement denoted through the subject’s signature. The artist has developed a ‘retrospective, post participation’ consent form to enable the subject to consent to their participation in the process of creation of ‘their portrait’ and subsequent exhibition. The retrospective consent form was produced from the University’s legal template.(8) Many elements are identical, but an additional clause is inserted: ‘You are invited to accept your participation retrospectively.’ (Slide of form)

Before describing the case study tests of retrospective consent, reviews of the Heuristic research model indicate it is an adaptation of phenomenological inquiry, but acknowledges the involvement of the researcher. Indeed, what is explicitly the focus of the model is the transformative effect of the inquiry on the researcher’s own experience. This terminology and the psychology research methodology points to applications in the field of fine art and photography for the artist researcher and the shared lived experiences with their subject. With this acknowledgement of the detailed methodology required for a robust analysis I present the truncated document of research inquiry.

Consent Case Studies.

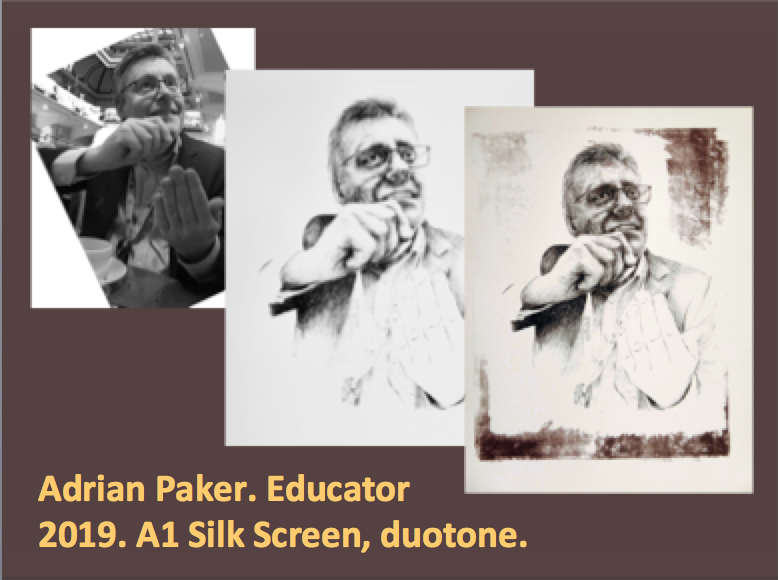

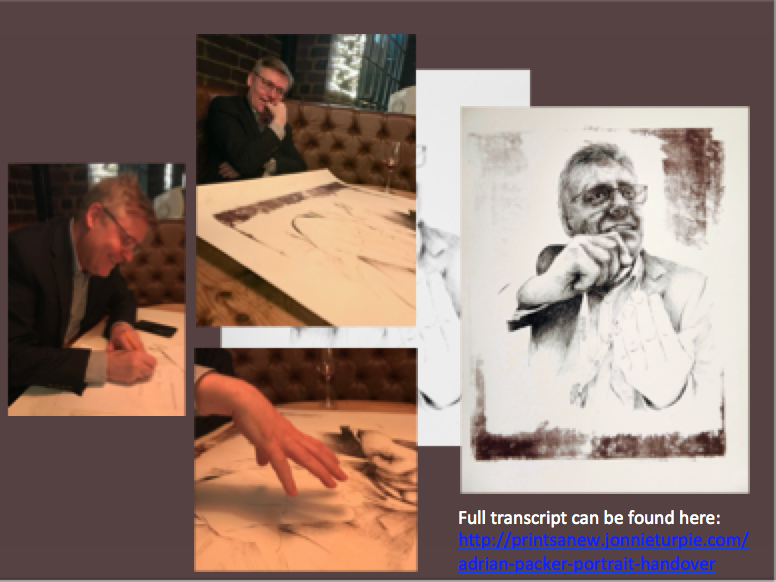

A1 sized drawn and printed portraits were shared with Artist Kevin Atherton and Senior Educator Adrian Packer CBE. The following are sub-edited.

[slides}

- Adrian Packer

The Artist texts Adrian: Are u around this week?

AP: Yep usual coming and goings, but I can flex. When works for u?

JT: Could do this or wed eve? I have a surprise/present 4 u.

AP: Sounds interesting.

Following the sharing the subject excitedly used his smart phone to take pictures of his portrait and shared it with his family, friends and colleagues.

“I get it. That’s what its about. Because you are trusting of the relationship between you and the subject, without asking for consent, before you go on to make the work. You are flipping it all on its head.”

The subject was animated and clear: “I understand the necessity for consent. But this joyous sharing is based on our mutual trust. I don’t want to read it. I’ll sign it. We trust each other. Your portrait shows that.”

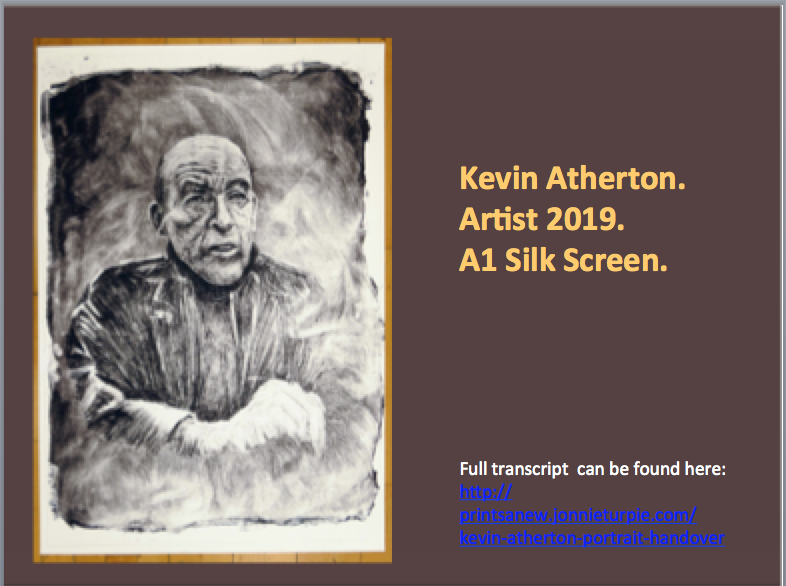

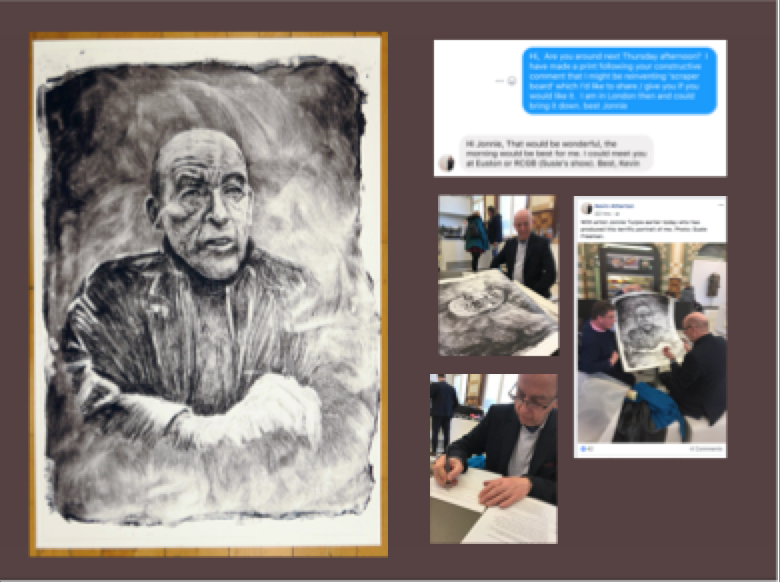

2. Kevin Atherton

We had recently met at the subject’s performance of ‘in two minds’. Over dinner we viewed recent portraits and Kevin commented that I was ‘reinventing scraperboard’. Inspired/challenged to make his portrait with this genre in mind, I took surreptitious smart phone photographs.

[slide of photograph.]

On completion of the drawn print I tentatively messaged the subject:

Hi, Are you around next Thursday afternoon? I have made a print following your comment that I might be reinventing ‘scraper board’ which I’d like to share / give you if you would like it.

An immediate message came back.

That would be wonderful, the morning would be best for me.

On asking if the subject would sign a consent form? He responded: “Do they make you get this signed?”

jT: “yes but I’ve developed a retrospective participant consent. But it will only be kept alive if you accept it and consent to it being made public. Otherwise I will destroy all traces of the portrait from photograph to drawings and completed print.”

KA: “I’ll sign anything. This is so good.” “It’s going to be framed. I love it. The background is a part of it. Its not just drawing or printmaking though. There are conceptual underpinnings in your methodology. Phone, drawing, print, sharing.”

The artist formally presented the portrait to the subject and he formally accepted. And Later posted on his public Facebook.

These two case studies culminate with signed consent forms. They are the individual and shared lived experiences of the portrait artist and subject. The underpinnings of research methodology in arts, social and psychological study including Grounded Theory; Discourse Analysis and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis referred to by (Frost, 2011.)(10) have informed this paper, but deeper analysis is required to both broaden and focus the research into Contemporary Portraiture in the digital photographic image world we inhabit and the lived experiences of the actors.

Thank you.

Bibliography:

(1) https://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidance/consent/how

(2) Chapter for Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Psychology – Willig & Stainton-RogersNarrative Psychology. David Hiles & Ivo Čermák De Monfort University, Leicester, UK and Institute of Psychology, Brno, CZ))

(3) Soussloff, C.M., 2006. The subject in art: Portraiture and the birth of the modern. Duke University Press.

(4) Eggum, A.,1989.Munch and photography. London: Yale University Press.

(5) The Economist Feb 28thPlanet of the Phones

(6) McKay Carolyn, ‘Covert: the artist as Voyeur’. Surveillance and Society 11.3 (2013)Thompson, G.L., 2009. How HBCUs will help rebuild America: A roundtable discussion. US Black Engineer and Information Technology, 33(2), pp.18-27.

(7) BCU Faculty of Arts, Design and Media

Research Ethical Review Policy and Procedures) : https://icity.bcu.ac.uk/Content/Document/02-ADM-Research-Ethics-Policy-and-Procedures-v-10

(8) Qualitative Research in Psychology Nollaig Frost

Frost, N., 2011. Qualitative research methods in psychology: Combining core approaches. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

The full exchanges can be found here: http://printsanew.jonnieturpie.com/adrian-packer-portrait-handover