MA Ethics presentation. 3rd March 2021. Edward Jonnie Turpie.

Images referred to in the presentation: http://printsanew.jonnieturpie.com/ma-ethics-presentation

Current research portraits: http://printsanew.jonnieturpie.com/portrait-prints-2019-20

Early research portraits: http://printsanew.jonnieturpie.com/people-involved-in-the-arts-2017-18

Research website: http://printsanew.jonnieturpie.com/

Thanks and Hello.

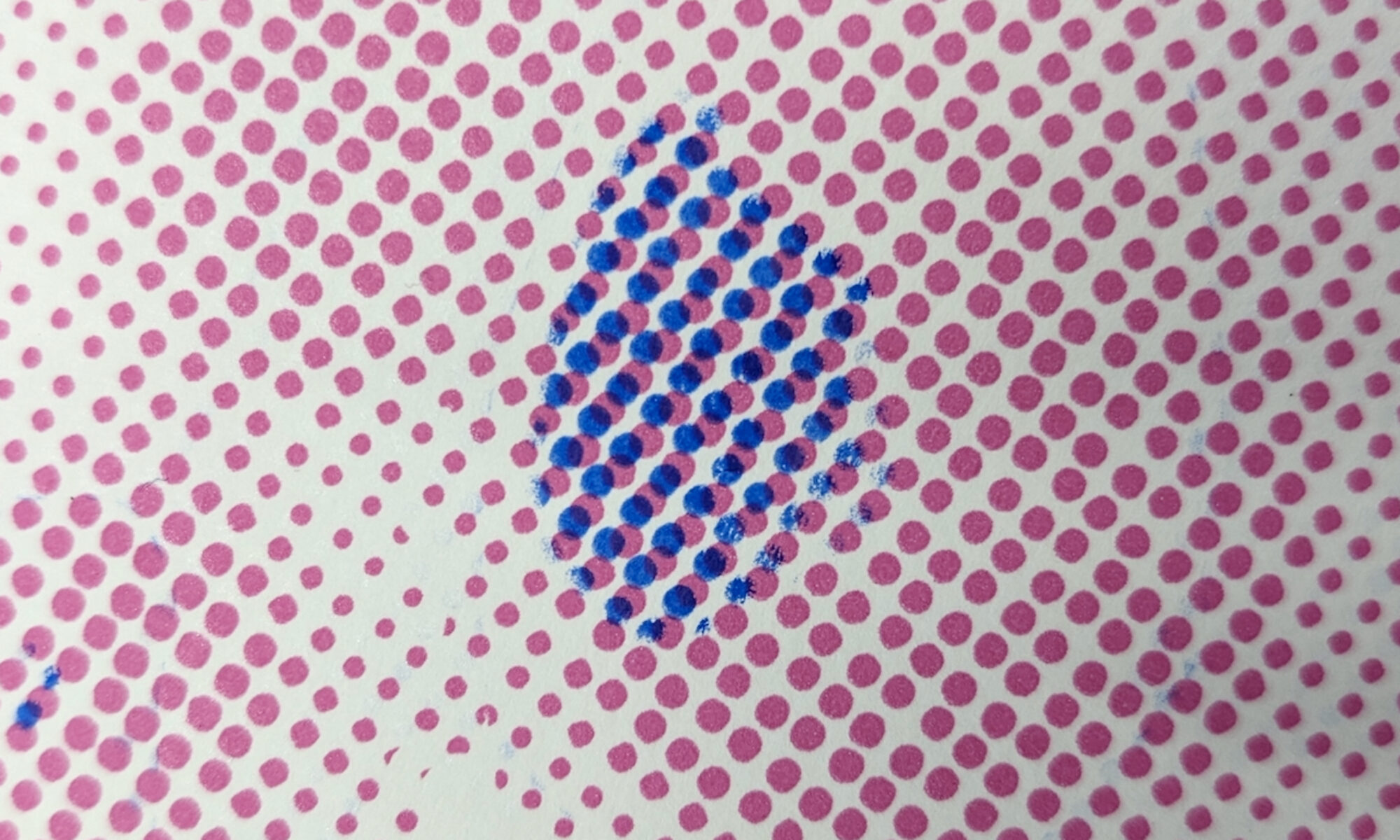

I’ve been asked to give you an insight into the ethical considerations of my PhD practice Research into Contemporary Portraiture in which I make drawn and printed portraits initiated from discreet smart phone photographs. Once the portraits are completed and printed, I contact the subject and offer them the first edition as a gift. As you will know form this programme there are many ethical questions raised by this approach. In order to carry out the research I have developed a method of retrospective consent which has been approved through BCU ethics procedures. This has taken over 12 months to compose, submit and gain approval. We can discuss the process and detail following the presentation. I’ve supplied some links to the portraits and to a series of photographs I refer to.

Applications of photographic imagery by artists and printmakers since the introduction of the medium, have been uncovered and create a lineage to contemporary smart phone photography. Building on this historic knowledge is research into the social and cultural implications of discreet smart phone photography and the ethical and legal issues of surreptitious image gathering. These investigations are providing emergent photographic discourses that influence and inform each other and provoke new knowledge in the domain of digital portraiture.

Post-feminist and post-colonial discourses posit that gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities (Alcoff,1991). These concepts provide a contemporary philosophical lens with which to interrogate the ethics of discreet smart phone photography, drawn and printed portraiture. In addition, research embraces the concepts of ‘lived experience’, through the heuristic research model and the phenomenological interactions between the artist, researcher, sitter, participant and smart phone.

Photographic Portraiture in The Western Context

In the context of globalisation and social media imagery, the doctoral thesis is from a diverse multicultural perspective, however the scope of the current report is limited to the Western traditions.

In a pre-digital age Susan Sontag wrote: ‘Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation.” This was an analogue environment where consumerist photography was in its populist infancy with photographic negatives posted to Kodak for processing and prints physically returned to the photographer for viewing and sharing. In the twenty-first century the instantaneity of digital camera technologies and social media has produced a tsunami of images of human beings made and shared in a global environment. Participation, intrusion, ownership, collaboration, ethics between subjects and producers alike is even more complex than in the analogue 1970s. It is in this context that this research investigates questions of contemporary portraiture.

Discreet and Surreptitious Photography and Art

‘The camera is clumsy and crude. It meddles insolently in other people’s affairs. The lens scouts a crowd like the barrel of a gun.’ So said Steve Barker in 2010.

To build a portfolio of portrait images for subsequent drawn prints smart phone camera photography is employed and in making these photographic references, surreptitious methods are adopted, to achieve a representative image of the subject, without their being aware of the lens and therefore ‘posing’, as indicated by Roland Barthes:

‘Once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of posing, I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image’(Barthes, 2000:10).

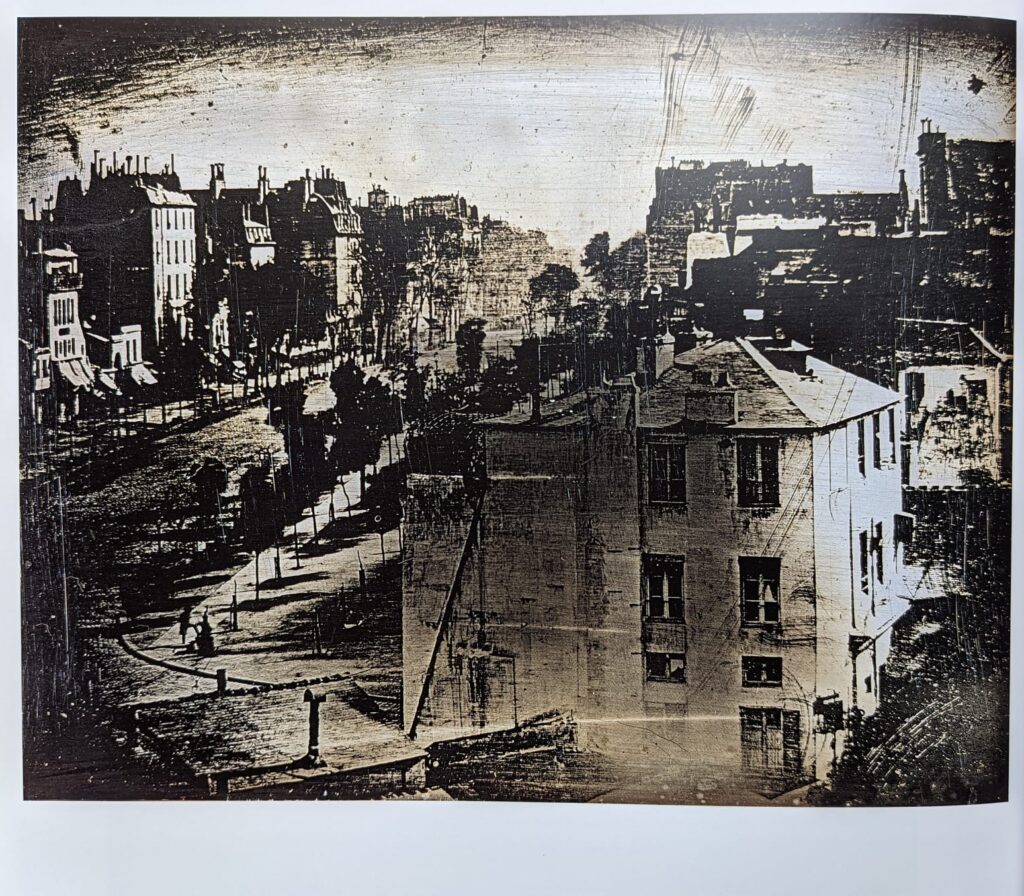

The earliest Parisian street images were captured in 1838 by Daguerre and presented to King Ludwig 1 of Bavaria as proof of the invention of the daguerreotype. It has been argued that the practice of photography was inaugurated with a surreptitiously-made image where ‘a man having his boots polished … is hardly likely to have known that his picture was being, in a very real sense, “taken”.’ As image capturing technology matured in the early twentieth-century, photographers and artists consciously applied discreet and surreptitious photographic methods. In spirits of enquiry, adventure and investigation, documentary photographers sought to expand their means of recording their subjects. In some cases, deceptive means to hide their intentions from their subjects were adopted. An example is photographer Ilya Ehrenburg:

For many months I roamed Paris with a little camera. People would sometimes wonder why was I taking pictures of a fence or a road? They didn’t know that I was taking pictures of them … The Leica has a lateral viewfinder. It’s constructed like a periscope. I was photographing at 90°.

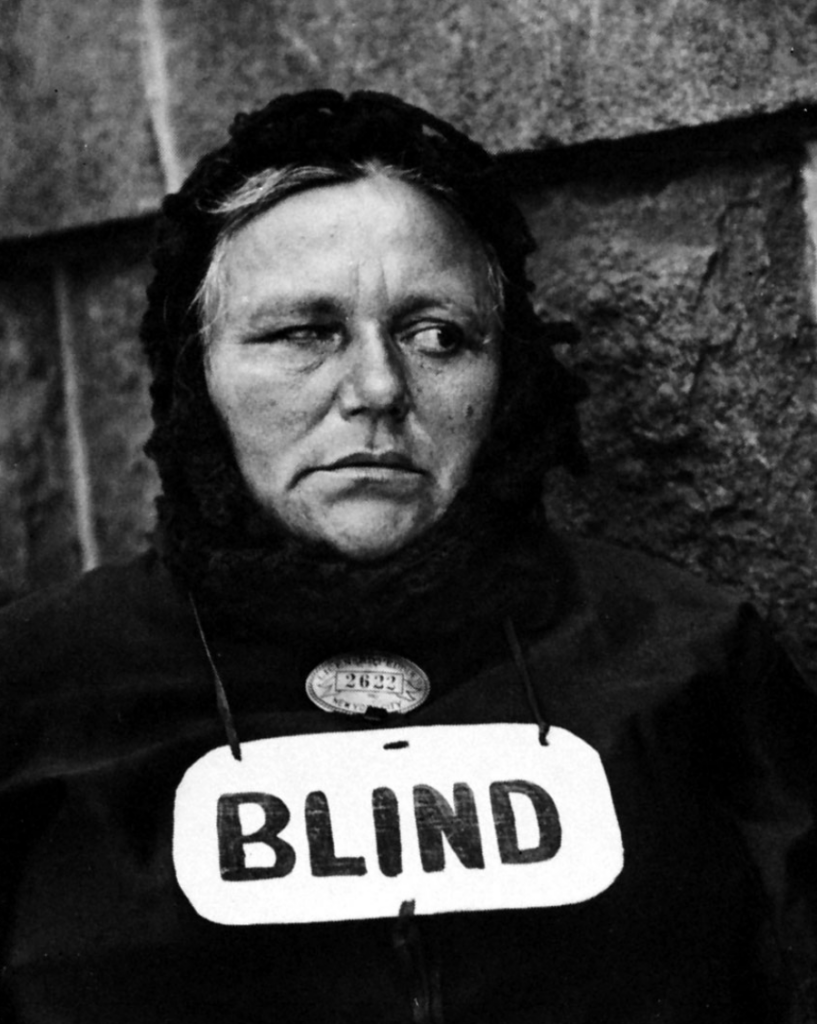

Ehrenburg compares himself with a writer: ‘A writer has his own notions of honesty. Our entire life is spent peeping into windows and listening at the keyhole – that’s our craft’. Ehrenburg was an early adopter of voyeuristic photographic methods with many others following, including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Helen Levitt, Ben Shan, Paul Strand, Cartier Bresson, Brassai and Wickes Hine. As technology and photographers developed, a variety of surreptitious methods of recording and ‘shooting’ were experimented with. It became easier to ‘take’ the subject by surprise when smaller cameras enabled street photography where no one at first expected it. It is reported that:

Early portable cameras were given a name: “detectives”. The design of the detective cameras was usually more fanciful than useful – one was designed as a stack of books, another a parcel; one fitted into a cane; another into an umbrella’s head or the heel of a man’s shoe. One camera was made like a revolver.

In the 1930s photographer Walker Evans put the case for discreet techniques: As he wrote to a friend:

Stare, it is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You’re not here long.’ (Garland-Thomson, 2009

Later he invited friend and photographer Helen Levitt to accompany him to the subway, where he outfitted himself with a camera hidden under an overcoat, a cable release running from the camera on his chest down his sleeve to his hand. Evans wanted to photograph people without self-conscious projection, in private interior moments.

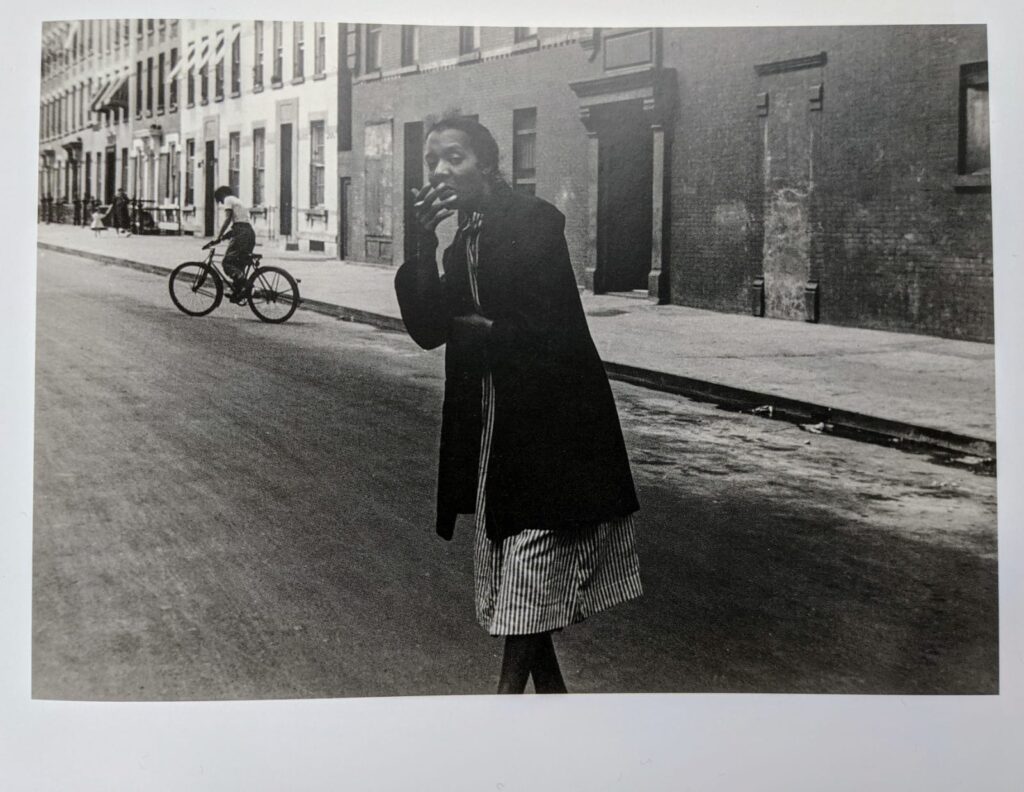

Contemporary artists have adopted surreptitious image capture. Nan Goldin photographed from embedded participation in intimate groups in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency and Philip-Lorca di-Corcia’s surreptitious recording of Heads with elaborate hidden flashes in the street which: ‘offers unblinking insight into unguarded, distracted faces of total strangers, capturing moments of absolute, impenetrable introspection on to which we can only project our own assumptions.’ (MoMALearning, n.d.)

As well as ethical considerations, such surreptitious acts have legal implications. Di-Corcia was taken to the New York Supreme Court by one of his unsuspecting subjects. In his defence he pleaded his first amendment right to exhibit a photograph of the subject that had been taken without their knowledge. US artist Barbara Kruger was sued for using a picture in It’s a Small World … Unless You Have to Clean It. A New York federal court judge ruled in Kruger’s favour, holding that, under state law and the First Amendment, the woman’s image was not used for purposes of trade, but rather in a work of art.

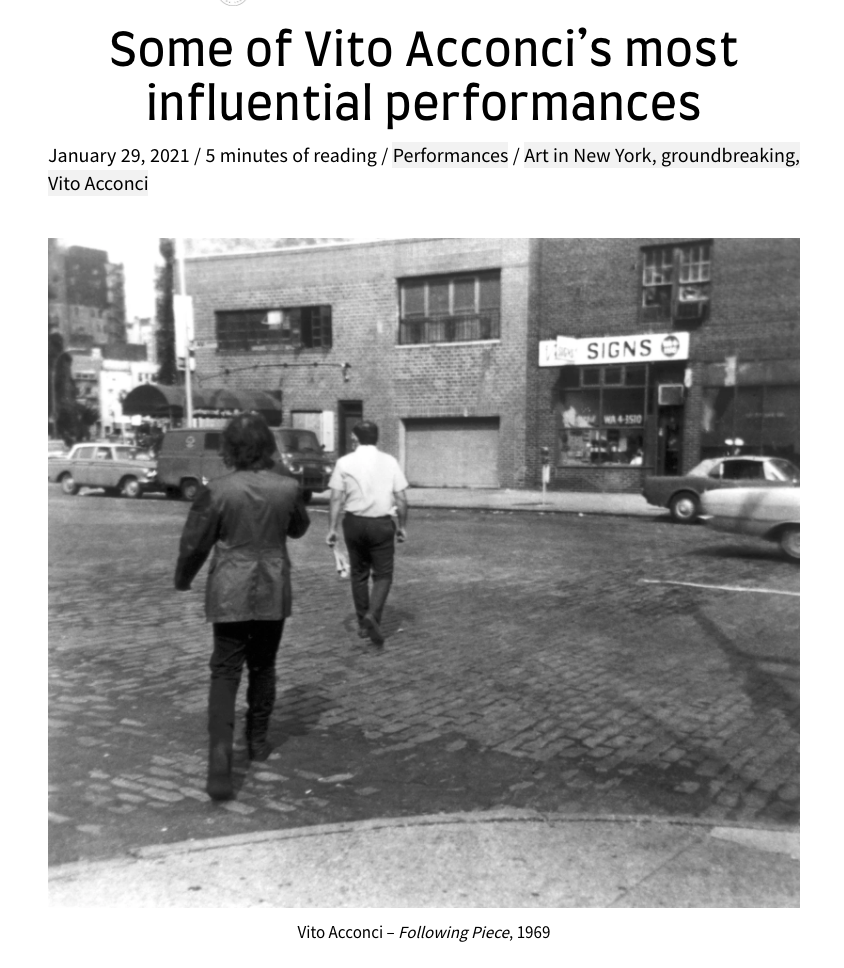

Artists have made surreptitious recording core to their practice. In Vito Acconci’s Following Piece, the artist follows (stalks) random people in the streets and photographically documents the actions until they reach a private space. In Sophie Calle’s Suite Vénitienne she follows a French man to a Venice hotel and secretly photographs his comings and goings. ‘She flirts with opposites: control and freedom, choice and compulsion, intimacy and distance. On one level, her art responds to the surfeit of choice in late capitalist society.’ Wrote Jeffries in 2009. She uses photography as a tool to document her artistic motivations to which she has commented: ‘Ultimately, my excitement was stronger than my hesitation.’

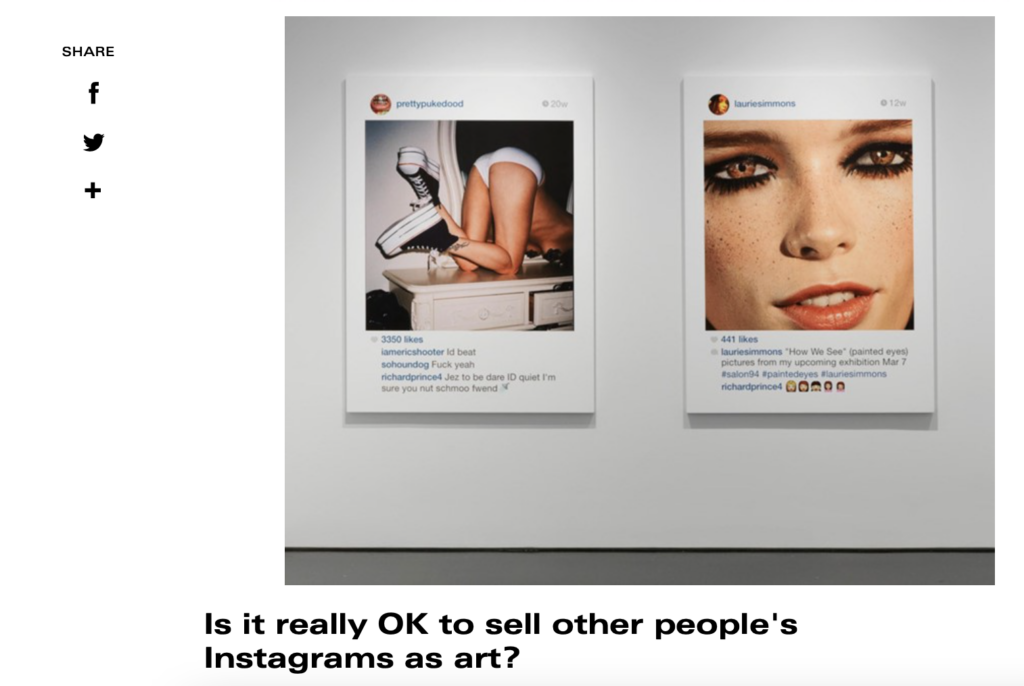

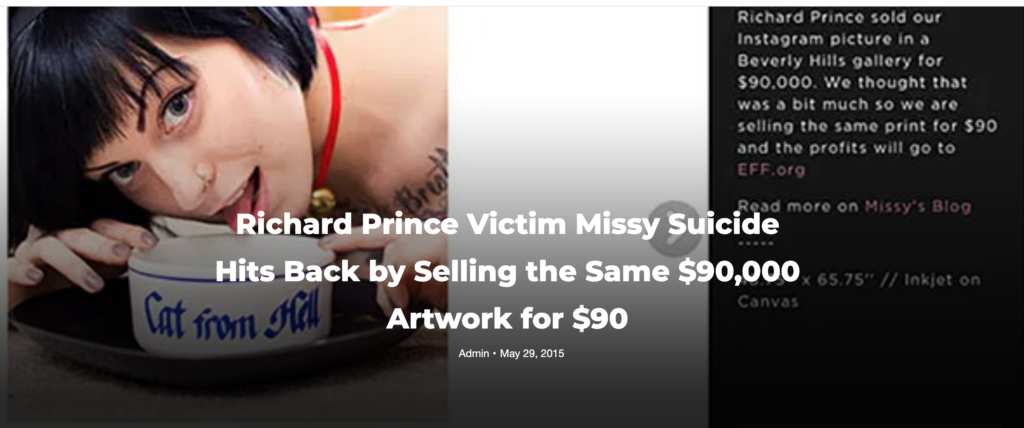

In the age of social-media a legal case centred on artist Richard Prince’s usage of images from the internet without consent and elicited comment: ‘Is Richard Prince a “trolling genius” or a plain old rip-off merchant?’ his New Portraits featured thirty-eight images he screen-grabbed from the ‘Suicide Girls’ Instagram channel, ink-jet printed onto large-scale canvases along with short social media comments. Prince has used ‘Fair Use’ copyright law in the past, which rules that if you tweak something enough, it can become something original. So Prince, by adding his own, rather distasteful comments, enlarging the images and exhibiting them in a refined art context argues he has transformed them. One of the subjects of New Portraits, Suicide Girls’ founder Missy Suicide, offered to sell her own prints for ninety dollars, with any proceeds going to charity. She took control of her image and exerted her right to, and ownership, of her image.

Most recently artist, photographer, writer Teju Cole published a collection of photographs and texts inspired by memories, fantasies, and introspections. This includes a photograph of a woman walking down a street from behind. On the facing page is the text:

I follow her for one city block. Thirty seconds after the first photograph, I take a second. Against my will, and oblivious to hers. I lose her to the crowd – the mutual danger is defused. On Instagram, the ones who see what you saw are called your followers. The word has a disquieting air.

Ethics of the Research

It is important to state that there are complex ethical considerations central to this research and core to the practice is that of participant consent. Informed consent means that participants voluntarily participate in the research with adequate knowledge of relevant risks and benefits. Providing informed consent typically includes the researcher explaining the purpose of the research, the methods being used, the possible outcomes of the research, as well as associated risks or harms that the participants might face.

For this practice-led research the completed drawn and printed portrait is finalised before the subject is aware of their participation. This is in order that the portrait is free of self-projection and reflective of a moment in time when subject and artist/researcher were in close proximity. Artist/researcher Carolyn McKay uses discreet media techniques to initiate her art works and tussles with the ethics of recording subjects without their knowledge and consent, and refers to Susan Sontag:

To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have.’ [. . . ] ‘there is something on people’s faces when they don’t know they are being observed that never appears when they do . . . their expressions are private ones, not those they would offer to the camera. (McKay, 2013: 343).

I concur with much of this statement, especially the first element that there may be something unique on someone’s face when they are not aware of being observed; the second may be more in question. This research takes the position that the artist/researcher is motivated to use a discreet methodology to achieve a starting image that is of a moment free of self-projection, which can become a portrait celebrating the subject’s persona as positively and artistically interpreted.

I have researched Media and ethics mechanisms that photographers undertake to achieve consent andcognisant and responsive to the value of participant consent in this artistic process and have submitted the first and second stage Ethical Review of Research Statement to the University’s Arts, Design and Media Faculty. (https://icity.bcu.ac.uk/hels/Ethics/Guidelines-and-Resources) This was approved on 11th December 2017. The statement has been reviewed, rewritten and submitted in 2019. It includes explanation of the research and to address the retrospective requirement an additional clause has been inserted: ‘You are invited to accept your participation retrospectively.’ With the addition that if the participant does not give consent all materials related to the portrait from smart phone photo to final print will be destroyed.

A valuable example of retrospective participant consent is that of ‘McFee’s Friends’ which places on researchers an obligation to ‘treat the “others” in one’s research as though they were one’s friends’ (McFee, 2010:155). In the spirit of friendship being based on a concern for the well-being of other persons, in addition to non-malfeasance, the further requirements are to protect one’s friends from exposé to debrief them about the research afterwards, and to grant them the rights of persons (e.g. privacy).’ (Mcfee cited in Fleming, 2013:39).

‘Mcfee’s Friends’ offers an additional retrospective consented framework for this research when the portrait is shared with the subject. The sharing is usually a heightened encounter but can be relatively straightforward when the artist and subject are known to each other. When they are not, a period of investigation can bring both parties together. This encounter is potentially charged where the personas of both are made real for each other. The documented trail of exchanges between artist and subject is an acknowledgement of the subject’s agreement to participate in the exchange of their portrait. Affirmative words of acceptance of the portrait are testament to a positive shared exchange. Anecdotal evidence in the form of email, text or face to face discussion is acceptable to both parties to agree the process of representation that has taken place, at first unwittingly, but finally together, making for a trusted mutual understanding and acceptance. The shared personal exchange of the portrait-making process is not a formal agreement of participation denoted through the subject’s prior signature, but more the artist’s as he signs, dates and titles the portrait in the presence of the subject, before gifting the first edition of the finished portrait to the subject. A formal consent can also be entered into.

The Position of the Artist Researcher

The gifting of the portrait could be seen to be an altruistic action on the part of the artist, indeed in gratitude to the subject who, by accepting, has granted the right to sign it as a finished portrait. However, there are further ethical concerns to be analysed. The artist researcher is a mature, white, european, male. This raises question of where he is located in relation to the subjects he represents from diverse backgrounds and identities that are not his own? These are questions of ‘positionality’. B K.Dautruche in 2016 States that positionality is defined as ‘a concept that gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relationalpositions rather than essential qualities.’ Linda Alcoff extends positionality with ‘location’, by which she means that the ‘social’ location of the author in relation to the other they are speaking about ‘has an epistemically significant impact on the speaker’s claims’. The artist researcher takes into account these philosophical, ethical and positional considerations in the decision as to whether a selected portrait should be photographed, drawn and printed. Final assessment of these considerations will be manifest at the point of sharing the completed portrait with the subject. Discussion between artist and subject elicits the relative positionality and establishes whether there is an imbalance between them that renders the action of portrait-making inappropriate, unwanted and to be stopped.

Thank You.