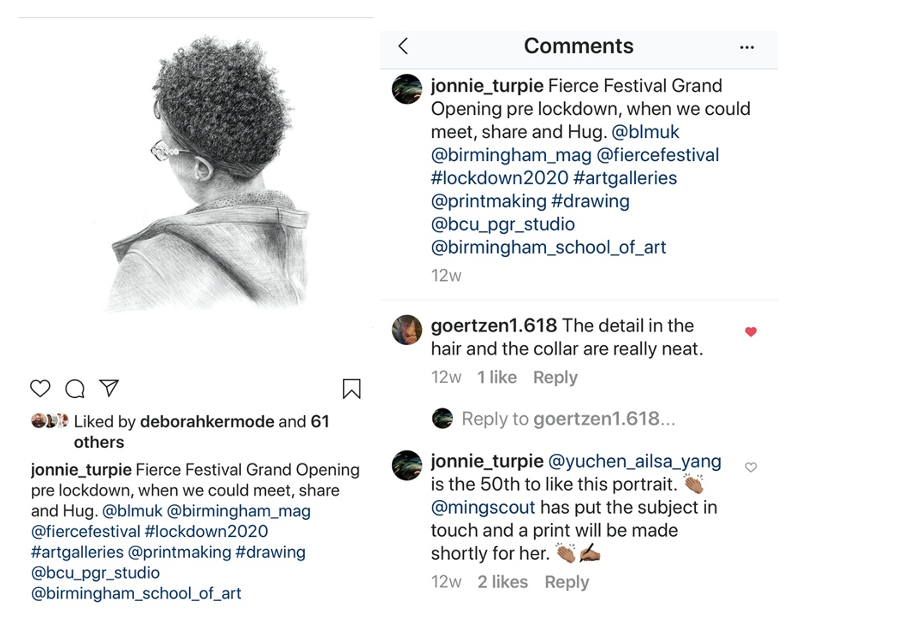

At the Fierce festival in 2019, held in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, I noticed an audience member in front of me watching the performance through her button adorned specs. The buttons were colourful in contrast to her dark curly hair and modern grey hoody fabric. To capture this beautiful and idiosyncratic head looking intently forward I took pictures from behind as a possible contribution to the series on art viewers and readers. I did not immediately make a drawing from the pictures, but downloaded and logged them for drawing time. Six months on, in Covid times and in response to #BLM I began a series of ipad drawings celebrating black people viewing in art galleries and this photograph was high on the list to draw. The contrasting textures of hair, glasses, skin and hoody were a challenge to use a variety of pencil marks on the electronic drawing tablet and programme. It was made over 3 days of drawing with regular reviewing and redrawing to get to an image depicting the subject’s attention to the performance, even though it was not included in the drawing, or referred to in any way other than her intent focus.

When complete the drawing was posted on Instagram with the BLM hashtag and the text: ‘when we could meet, share and Hug.’

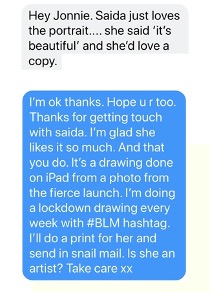

Following the posting the photographer Ming DeNasty messaged me to say that the drawing was of ‘Saida’, who she had photographed for an LGBT exhibition.

Social media has the capacity to make connections in unplanned and unpredictable ways. This connection already felt positive because of the feedback and that it had been facilitated by a mutual friend even though neither of us knew each other.

After a couple of failed attempts to connect, Saida and I managed to arrange a visit to present her with her portrait. Before I went round she had checked my insta and left a comment on her portrait – ‘I think this is me hehehe’.

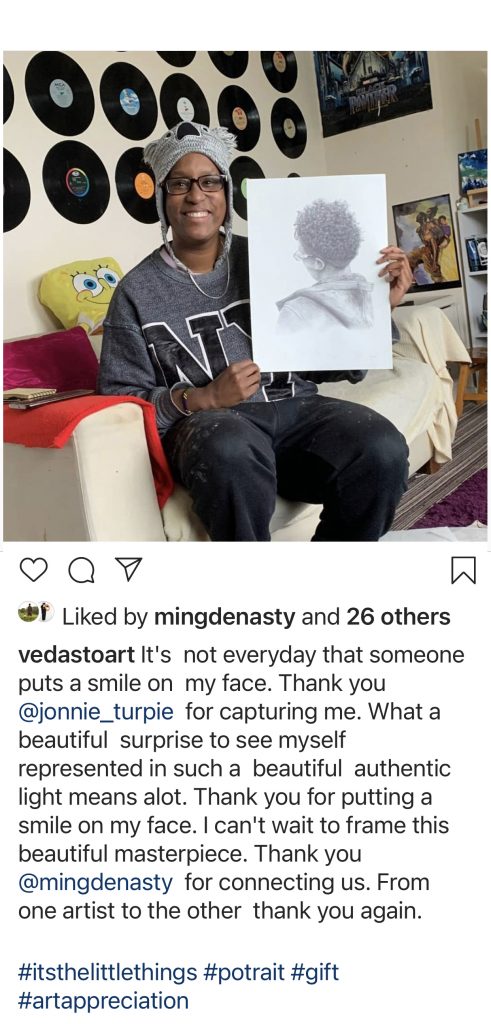

Saida was super welcoming with tea biscuits in her exuberant flat full of art and music, including her wall of favourite vinyls. Looking out over a grey day in South Birmingham was countered by her bright and colourful book of photographs from her work with primary school children. Her love of abstract art was resplendent as the beaming children enjoyed making shapes and colour under her tutelage. Saida is doing a psychology and art degree to qualify as an Art Therapist.

Her love of children was clear as we sat across the room. I explained that I had noticed her buttons at the Fierce Festival Launch and loved the way they contrasted and complimented her hair, skin and hoody. We discussed the pain of the enforced isolation imposed by the virus. She shared her situation of additional grief at the loss of her mother only months before coronavirus struck. Her Mum was a Christian from Tanzania and her father a Muslim. In Islam people must be buried quickly. This was painful as Saida had only got to know her mother for the three months prior to her death. She explained that she had been brought up in Birmingham by her mother’s sister. Her thirteen-year-old brother was still in Africa, but now without her Mum. Saida is to invite him over to live in Birmingham with her until he’s old enough to live on his own.

This is a tough life experience and Saida is still getting through the grief. As ‘My Name is Leon’ the novel by Kit de wall, read by Lenny Henry, is still ringing in my mind I suggested it might be a good book to read or listen to. It might help share the load as Leon was brought up by his Mother’s Sister and he had a little brother Jake. On thinking further, I also suggested another book: ‘My name is Why,’ Lemn Sissay’s autobiography of his life in care. We shared my drawing of Lemn’s book signing which Saida enjoyed as it was a positive moment captured, even though we cannot see Lemn’s face, but we can see the many faces of those waiting for his signature to remember the day he shared his painful, but ultimately positive memories.

Having shared some history, it felt like the right time to offer Saida her portrait. In a socially distanced way I handed an A3 cardboard envelope to her. This is a charged moment as the revelation of the physical picture is the point of realisation of the physical portrait image. Saida carefully pulled the drawing and its tracing paper cover from the envelope. She held the image up to see it and was clearly moved by seeing it before her. She was moved to tears. I touched her arm to share the moment and recognise that the actuality of the drawn portrait was an emotional experience. Unwittingly and naturally we hugged. An important hug in covid times and a reminder of the Fierce Festival when everyone could hug without fear. We returned to our socially distant seats and continued to share the moment.

“I must take a picture.” I said. Saida made to take her spectacles off and I exclaimed: ‘Don’t take your specs off! The buttons!’ Following the photo Saida rose to find a card and presents she had put together for me. I was now welling up. What a deep sharing experience this is. Some may question the ethics of taking candid or surreptitious pictures to make portraits from, but this experience once again confirms that the process that ends with the sharing of the finished art work can elicit extremely positive human experiences. I got the feeling that Saida felt recognised by my act of portrait making. We had talked about the value and necessity of making visible black people and this was a small contribution to that. Her emotions seemed to talk of her being valued through the celebratory portrait, observed and made by someone not known to her, but now shared between us. I was equally moved by the warmth of the moment, that the iPhone photo can’t capture, but is a valuable memory of the shared experience.

Later I shared the photograph of Saida with her portrait, by text and she reposted on instagram.