The Making of the printed portrait

A recent silkscreen portrait was of artist Yuchen Yang. Having drawn the portrait and prior to printing, consideration was given to whether adding additional marks might enhance the image and point further to the subject’s own artistic processes. This was an opportunity to experiment with visual mark making beyond the figurative mimetic realism of the drawn portrait. Could additional marks add to the portrait and reflect more of the artist’s perception of the subject’s personality? Alternatively additional marks may be to the detriment of the visual experience of the original drawn image. The following exploration was an opportunity to extend a range Material Encounters* in the formation of a new portrait image.

Yuchen Yang. Final A2 Drawn Silk Screen Print on Canaletto paper.

Chance leads to dots of absence.

The portrait of Yuchen Yang began with a ‘realistic’ drawn, then printed portrait. Additional marks were made by brushing vine black ink, in gum Arabic, on to mark resist film. Beading marks formed from the brush strokes as it was repelled from the film. However, an unconscious, chance occurrence took place during the printing process. When preparing to screen print a first test pull on newsprint or tissue paper is made. This is a quick, ‘last chance’ proofing method to assess the integrity of the image before printing an artist’s proof (*) and edition on heavy, high quality and expensive art paper.

The printed image on this test is usually relatively thin as it is the first pull and the ink has not built up on and in the screen. The flimsy semi transparent tissue paper is not intended as a finished final print, however the confluence of the two materials creates a delicate, object and image relationship.

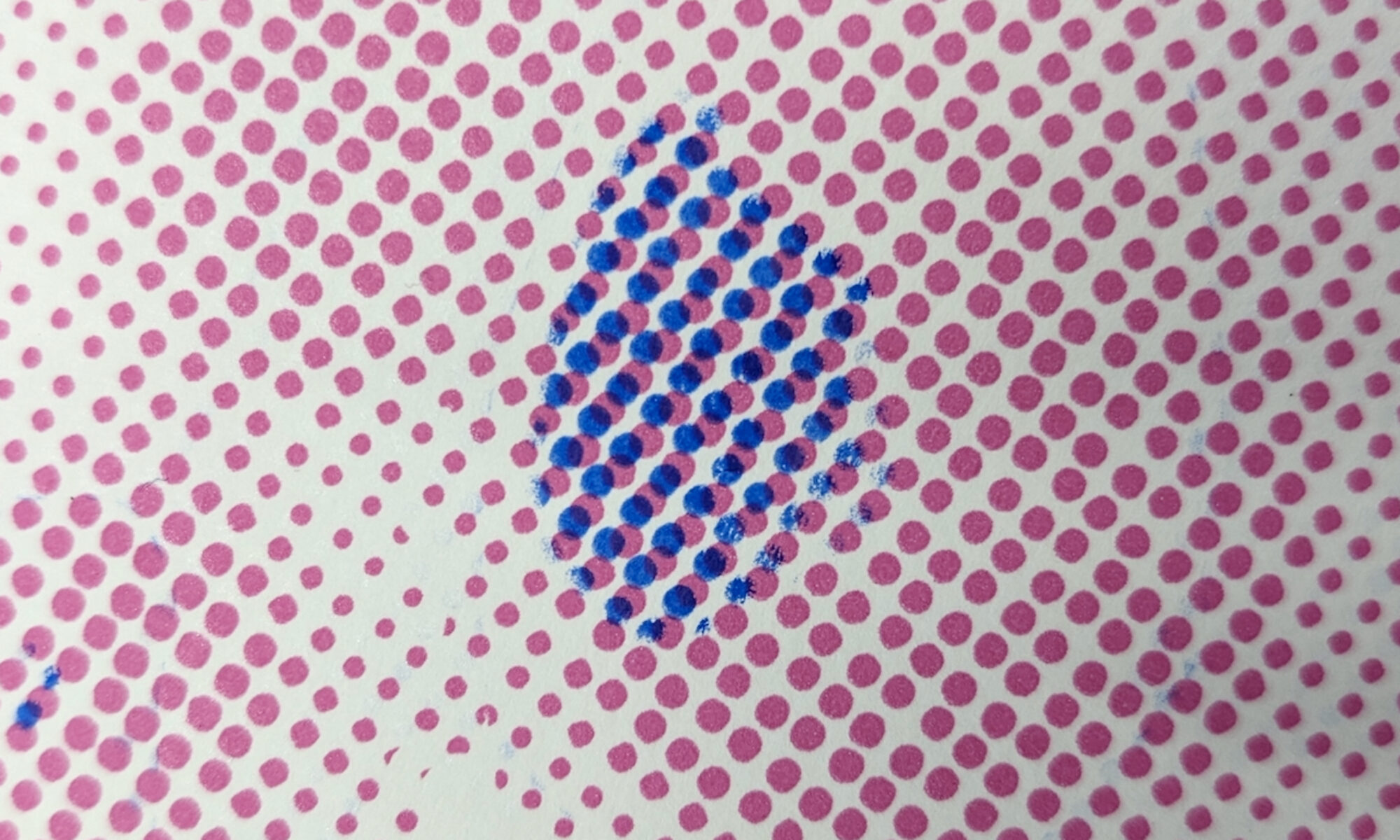

On this occasion the tissue proof revealed a matrix of empty dots that correlated with the screen bed’s vacuum system. This is a system designed to hold the paper securely in place during the printing process. As the tissue paper is flimsy the strong vacuum airflow through the holes in the screen bed pulled the tissue into them. The small distance of approximately 1mm between tissue and screen means the ink does not reach the tissue, and leaves it blank. An absence of ink, and therefore absence in the image creates an unplanned patterned ‘dot’ effect on the portrait. This chance visual effect was enticing. It was not intended nor anticipated.

Yuchen Yang. Silk screen and Vacuum dot on tissue paper

The blank dot matrix gave a new visual element and a new iteration of the printed portrait. The embedded ‘dots of absence’ reveal the process of mechanical reproduction undertaken to make the work. They further articulate the conditions of making the print on that particular day, complete with particular atmospheric conditions, on a particular screen bed, with particular viscosity of ink, with a particular application of squeegee pressure in a particular wider environment. Such variables, came together to create ‘patterns of dots of absence’ that were worthy of noting and preserving with potential for future applications.

The patterned dot effect on the portrait’s overall printed image was not unlike the digital tracing marks on faces being mapped for digital motion capture. The dots did not feel like a mistake on the subject’s face. They were not harsh digital dots, nor a uniform mathematical matrix producing a sharply scientific facial manipulation effect. They added a new texture and potential interpretation to the portrait: perhaps more modern, more questioning of figuration. The soft dot of absence seemed to align with the subject’s interest in Japanese digital visual culture and modernity and therefore could be considered as contributing to the portrait interpretation.

The chance encounter prompted further enquiry into related materials, marks and interpretations. Could the ‘vacuum dot of absence’ occurrence be achieved repeatedly? Not only by chance, but be predicted and applied in future printed images.

When viewed at a distance the tissue portrait is perceived as a realistrepresentation, however on closer viewing the dots come into focus. As they are retained and included, they have been decisively chosen, by the maker, to be there. They are not a mistake. They are there for a reason. They point to, or reveal more of the artist’s drawing and mechanical printmaking process. In the artist’s judgement they must be adding to the portrait.

A further variable is the positioning of the paper. By varying the position the dots appear on the darker areas of the image increasing their visibility. This variation affords the maker additional aesthetic choices. More pattern, or less? More dots or less frequency? Being more apparent through the contrast of empty pockets of absence with the ink-laden shapes and shadows, that convey the drawn face’s unique contours and recognisable elements.

The rationale for the portrait is to celebrate the subject through an artistic interpretation, not simply to make an accurate realist document. Being open and vulnerable to chance encounters through the drawing and printmaking process may lead to additional aesthetic and representational benefits to portrait interpretation.

Openess by the printmaker to the semi complete print has precedent: Maculature:‘An impression made from an intaglio engraved plate to remove ink from the recessed areas, [using] a sheet of waste paper or blotting paper.’ (7) This technique and use of waste paper materials were experimented by Rembrandt and are described in The Unfinished print(8): “Rembrandt’s alteration of meaning through variant printings and through powerful reworkings of the plate is yet more startling in the Three Crosses, 1655 …… a significant number of impressions, often with distinctly different wipings, were printed on a variety of supports at each stage. In addition to more common papers, he used very delicate, tan coloured oriental papers, a course stock known as oatmeal, and sometimes vellum.”

Beyond his selections of paper he went on to a fourth state of the Three Crosses: “[it] is an entirely different work forged on the same plate. Yet like a palimpsest*, Rembrandt’s original scheme is still visible in furtive details that linger beneath the heavy scoring of the copper in this final stage. …… The ability to accomplish such extraordinary revisions within a single arena […..] is a benefit peculiar to intaglio printmaking. In Rembrandt’s work this makes the question of finish uniquely problematic and prophetically modern.”

Indeed these 17th Century material experimentations employed to create and alter meaning for the figurative artist, indicate a vulnerability, openness and enthusiasm to the making, in the making of printmaking.

In modern day printmaking photographic processes are used by artists to create and make fine art prints. They may be technically accurate in their digital or electronic systems, however they can be combined with haptic, human means of creation and together be open to chance and surprise opportunities. These individualized practices can lead to unique bespoke artifacts and in my practice printed portraits.

The bespoke drawn and printed portrait has a valued place in a 21stC digital screen world, as it has uniqueness to it born of the eye, hand and brain of the drawing artist. It is an artifact, not necessarily an accurate recording of the subject, but an interpretation of the subject by the artist.

Contemporary Printmaking artist Margaret Ashman describes how she applies digital photographic techniques in making her emotionally charged prints(5): “I capture Micro expressions with video stills or digital photography, which are used as sources for my photo etchings……… I combine photographs with digital layering in adobe photoshop, producing a single digital colour image. I then split up the image into layers, using channels and bitmap mode, to produce a set of printing plates. I then ink these in different colours to recombine them in a single print. When I bitmap my images I use diffusion dither, the most random bitmapping option available. I set the dots per inch between 100 and 220. Sometimes I print the bitmaps on my home A3m printer and enlarge them to A0 size by photocopy: these photocopies have to be oiled to turn them into transparencies for photo etchings.”

This description of multi layered, complex processes, managed by the artist, point to a range of moments where vulnerability to making, in the printmaking, can be opportunities for chance to play a part in the resultant image. These imaginative and inventive moments interspersed with technical processes are material encounters where the artist is exposed, and can be open to, accidental, yet fortuitous creative decisions in printmaking.

The purpose of the drawn and printed portrait

The portrait maybe a memory; a token; a celebration; an accurate depiction; a record or a ‘lasting memorial’. This last criterion was voiced by Albert Durer when declaring his intention to engrave a portrait of Martin Luther in 1520. According to David Hotchkiss Price (2003), the point of Durer’s portraits was to ‘preserve the appearance of people after they had died’. 1 500 years later I find myself asking the question: What is the motivation to make drawn and printed portraits? With the prevalence of photography and the ubiquitousness of smart phone selfie portraiture there is no reason to preserve likeness for people when they have died, personal snapshots, digital albums, Facebook and Instagram can achieve that for everyone.

However, in the 21st century the bespoke drawn portrait has an important role in our screen lives, as it has uniqueness born of the artist’s eye, hand, brain. It is a unique artifact, not necessarily an accurate recording of the subject, but, instead, a subjective interpretation of the subject. The artist, by applying drawing and printmaking skills develops individual abilities and perhaps a style. However these can become habitual. The dots occurrence signifies a disruption to habitual methodological approaches. Being open to material chance enables the artist to be alert to oppportunities for interpretation and representation within the context of making

By taking a photograph as a starting point the drawing artist embarks on a selection of what is important to include, or exclude, in their chosen subject. American artist Andrea Bowers draws scenes of protest from photographs. She omits ‘information’, creating areas of blank paper thereby reducing the pictorial content to focus on what is important to her. As Peter Kalb (2015) suggests: “[Her] act of representation is not determined by an a priori structure, but is a product of the artist’s ability to apprehend and decipher portions of the image.”2

She believes that her attention to the process of drawing shows respect for the subject, by retaining the photographic realism, but breaks its realism in search of a favoured interpretation.

Stephen Farthing in Recording and Questioning of Accuracy (2008) (2) brings a further insight into the drawing artist’s considerations (p.145 ): “It might seem reasonable to assume that drawing made in the presence of what they depict would emerge at the top of the accuracy scale. But in reality this is not always the case. Accuracy is not just a question of skill it can also be affected by honesty, free will and genuine mistakes.”

This is the point at which I am in the research and investigation of methods of making drawn printed portraits originated from smart phone photographs. A bridge over which one might traverse to embrace mistakes that improve and augment the representation of the subject, all within the terrains of position, social location, honesty and free will, through subjective interpretation.

A central element of my practice is establishing a methodology of sharing portraits with the subjects. Portraits originate with a discreetly ‘taken’ smart phone photographic image. Drawing, with graphite on mark resist transparent film for transfer to silkscreen, is pursued to interpret the subject beyond the initial photograph. The final large scale image is silk-screen printed on selected fine art paper. Upon completion, efforts are made to share the final artifact with the unknowing subject. This creates a circle of sharing that is a pleasurable surprise to the subject, whose enjoyment and acceptance of their portrait is a moment of contentment and guilt effacement for the artist, for the potentially fraudulent nature of the initial ‘taken’ image.

It is also an exchange that is a site for questions of ‘positionality’, raised through the act of representation undertaken by a mature, white male artist of subjects from a diverse range of backgrounds and identities. B.K. Dautruche (1) states that Positionality is defined as “a concept articulated by Linda Alcoff, and others, namely that gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities.” Alcoff (2) extends positionality with ‘location’. By which she means the ‘social’ location of the author in relation to the other, they are speaking about.’ This philosophical consideration may be applied to the portrait artist as they decide to embark on making the artifact. One which may be further tackled at the point of sharing the completed portrait with the subject.

Dautruche goes on to observe that in relation to debate and theorising: “listening within a stance of openness maps out an entirely different space in which to relate discourse.”(3) (Ratcliffe) Applying this openness to discourse is important in writing or speaking of, or about others. Such openness may also be important in visual representation of others and in this case the making of drawn and printed portraits, to be shared and exchanged with the subject. Additionally openness and vulnerability to the making, in the making by the artist can illuminate space for creativity.

Being open to the materiality of paper in printmaking

Returning to the dots of absence my research has shown that the chance vacuum dot matrix can be replicated on tissue paper. More experimentation is required with print papers to assess the extended opportunities this now provides. However, working with light-weight papers brings a more delicate and careful ‘feel’ to the printmaking process. From the first moment of bringing the paper to the large mechanical screen bed; stroking it flat with the palm of the hand, before the vacuum sucks it flat, ready for the screen mesh to be brought into close contact; papers are handled with extreme care. The squeegee bears down, with necessary pressure pushing the ink through the mesh on to the paper, awaiting the snap of the screen away from the printed image it has delivered onto the paper’s surface.

The capability of tissue paper to be manipulated in tactile material ways is at odds with the norm of making fine art prints on sturdier paper. Quality heavyweight paper is handled with extreme care throughout the print process. From the paper store to the print bed, print racks to plan chest and maybe to the framers table, the paper is painstakingly kept flat. Maintaining the uniform quality demanded of the editioned prints, bereft of creases, dents, blemishes, tears or unintended marks is part of an essential dialogue the maker has with his/her materials

However, the tissue print is fragile and inconsistent from the onset. The paper doesn’t land on the print bed or rack, but drifts with air flows. Once printed it is ‘glided’ to the bench with care. Still crooked and crumpled with drying ink tensions. Making it flat to show the portrait image at its best, brings a new satisfaction beyond the customary heavy weight paper landing on the bench, which has its own material satisfactions.

Seeing the portrait on transparent tissue inspires another uncharacteristic interpretation. The print may not be destined for the framers, but could be hung on a window with back-lit sunlight illumination attending to the materiality of the paper dictated by the conditions; the dot matrix takes on a more prominent position.

Being further open to the making, in the making, paper was hung from a corner on a window. The tissue’s weightlessness allows the portrait to ripple or pleat like a piece of cloth; a transparent ‘fabric’ print; with the print adopting a three dimensional ‘unframed’ presence. If the print was formally displayed in this manner it would be clear to the viewer that it was intentional, and they be encouraged to look around and into the portrait.

Surprise Serial Effects.

Being transparent the tissue allows a number of prints to be placed in front of each other giving a further interpretation: repetition, reverberation. This concept presented itself, again by chance, as the tissue prints lay on a lightbox. They were ‘off register’ making a serial staggered image, not unlike the ‘feel or ambience’ of the original dot matrix chance occurrence. Extending this option made ‘in line serials’ of repeat portraits. Additionally, positioning of oppositional prints, i.e. left faces right and vice versa, created a more abstract portraiture. Yet further material encounters to be open and vulnerable to.

To Conclude:

Fundamentally the material chance encounters in printmaking, that have been explored, have led to the drawn and printed image as a singular artifact in its own right; rather than the original intention to produce an accurate portrait using conventional, repeatable print editions.

Being open to the application, adoption and unexpected properties of materials, unforeseen methods and chance encounters during the making, enables the artist to be active and responsive to the processes of printmaking. New, unforeseen unpredicted visual opportunities can be spotted, recognised and evaluated during the making. They may offer enhancements to the portrait they had not predicted, nor anticipated. In coming across them, by chance, the artist can accept, or reject as they pursue their task of interpretation.

Having followed the creative processes described, and the prints made to the artist’s satisfaction, the final portraits can be shared and offered to the subject. The acceptance by the subject is an important ethical and philosophical event that reflects the equality of artist and subject in the making of the portrait.

Finally, being vulnerable to the making, in the printmaking has made manifest multiple encounters and engagements with the materiality of the drawn and printed portrait.

References:

1 Bodeline [Bo-duh-lean] K. Dautruche. Why Positionality & Intersectionality are Important Concepts for Rhetoric In My Most Humble opinion. https://bkdautru.expressions.syr.edu

2. Ratcliffe.K. Listening

(-) Linda M Alcoff. Problems of Speaking for Others. Cultural Critique No 20. 1991/2 P7

(-) Dyson.A. The Printmakers’ Secrets. Margaret Ashman. A&C Black ltd. P20

(-) Maculature. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/maculature

(-) The Unfinished print: Parshall.P, Sell.S. Brodie.J. National Gallery of Washington. Lund Humphries. 2001 p53

(-) Price, D. (2003). Albrecht Durer’s Renaissance, university of Michigan Press p225

(-) Pergam, E.A. ed. 2015. The Politics and Poetics of Contemporary Practice. Ashgate. Peter Kalb. Drawing in the Twenty-first Century.

(-) Writing on Drawing. Ed Steve Garner. Intellect. Ed Steve Garner. 2008. Intellect. Chapter 9 Stephen Farthing, recording: And questions of Accuracy.

- Material Encounters Research Cluster. Birmingham School of Art

MATERIAL ENCOUNTERS intends to extend and interrogate the boundaries of materiality within the context of contemporary art. The centre provides a critical intellectual space for the exploration of embodiment, subjectivity and aesthetic practices as they are encountered through material and theoretical investigations. Central to the discourse between the researchers is a shared commitment to examine the possibilities and unknowns of matter as a critical meeting point between thought, intention and the expectancy of what might transpire. The centre researchers occupy a broad territory across contemporary art theory and practice embracing cultural exchange and collaboration with scholarly partners both within and beyond the academic environment. This diversity facilitates a thought-provoking and richly discursive situation contributing new thinking and insights to an international community of researchers in contemporary art.

* WHAT IS AN ORIGINAL PRINT? https://www.scribd.com/document/55070770/Print-Making

An original print is the printed impression produced from a block, plate, stone or screen on which

the artist has worked. By choosing to use a fine art print medium, it is possible to produce a

number of identical images, each one a hand-made original by the artist. Normally there is a

separate inking, wiping and printing of each color and for each copy within the edition.

The total number of prints is predetermined by the artist and thereafter; the blocks, plates, stones,

or screens are destroyed or recycled so that no further impressions may be taken. Only in modem

times have editions been limited to make them more desirable as an investment. Each original

print must bear the signature of the artist (usually in the lower right-hand comer or margin) and

also an indication of the total edition and serial number of the print.