In January 2019 I moved into the downstairs Studio at Moseley School of Art with Artist Mohammed Ali of Soul City Arts. We share the studio and participate in the forward direction of the regenerated 1900 Art school that was originally built to provide local education in the Arts.

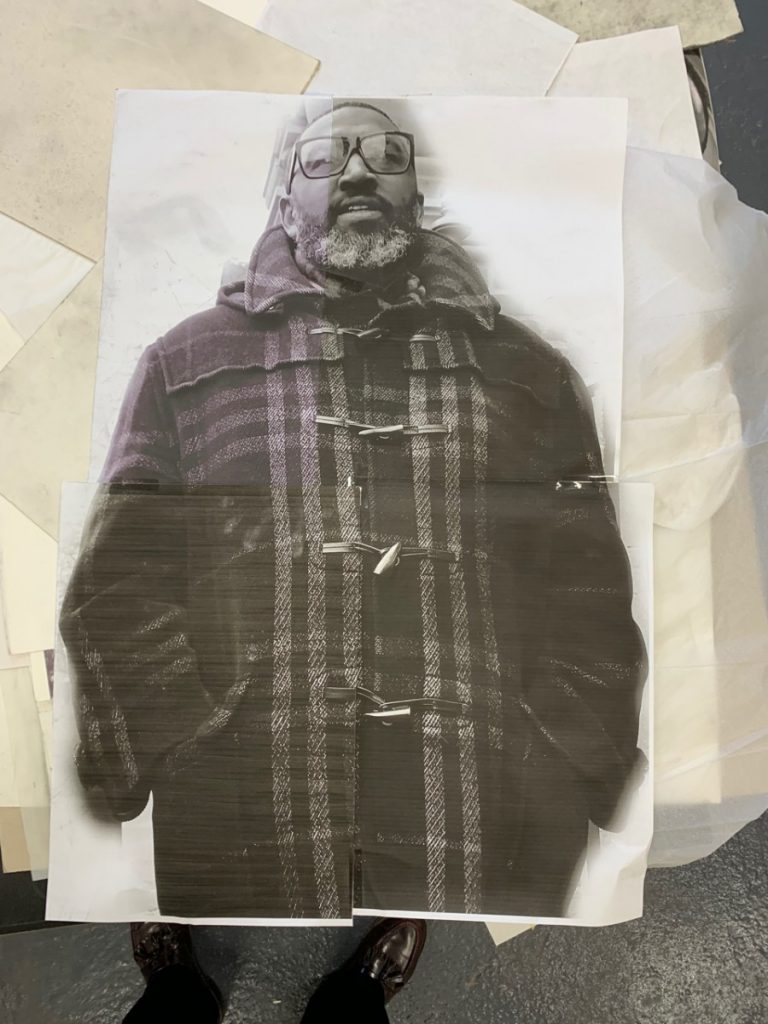

On a cold February afternoon Mohammed and I were discussing with Afzal the carpenter, the external boards being erected on the building facade when an imposing gentleman approached and said hi to ‘Ali’. Ali introduced ‘Hamza’ to Afzal and myself and he asked what is going on in the building as he had noticed it reopened. He had spent time in education classes in the building many years ago as a part of the centre for the Moseley Muslim Community Association. During the conversation I made a smart phone photograph of Hamza as he stood before us in his warm patterned duffle coat.

On reviewing the photograph I was impressed by the image as it reflected the imposing and serious impression Hamza had made on me. Later I shared it with Mohammed during a discussion about the hadiths concerning the making images of the human form and of portraits in Islam (hadiths are records of the traditions or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, revered and received as a major source of religious law and moral guidance, second only to the authority of the Qurʾān ) . There are current academic and scholarly discussions about the appropriateness of drawing, painting and photographing of the human face. There are a range of interpretations and nuances to the debate ranging from the wholehearted support for no figuration through to acceptance of representation in the contemporary world.

While photographs of the human face may be acceptable, especially for legal and public administration uses, a number of the hadiths discourage the drawing of the human form by humans as it can be interpreted as a form of idolatry and imitation of the creation of Allah. Some clarifications suggest that excluding the eyes from drawn portraits may be acceptable as the viewer of the image will not be able to see into the soul of the subject.

Mohamed was impressed by the stature of Hamza in the photograph and rang a mutual friend, and convert to Islam to ask if he thought Hamza would be interested (or offended) by the proposition to make a portrait of him: “I think he will be interested, but you will have to ask him.”

In the photograph Hamza wore heavy rimmed spectacles, reflecting the surrounding light and obscuring much of his eyes. Maintaining this covering of the eyes, and the potential to see into the soul, could be achieved in making a drawn portrait. Mohammed bumped into Hamza in the street and told him that I was interested in making a portrait of him based on a photograph I had taken. Initially he was surprised about both elements of the proposition, however he said he would review it once completed.

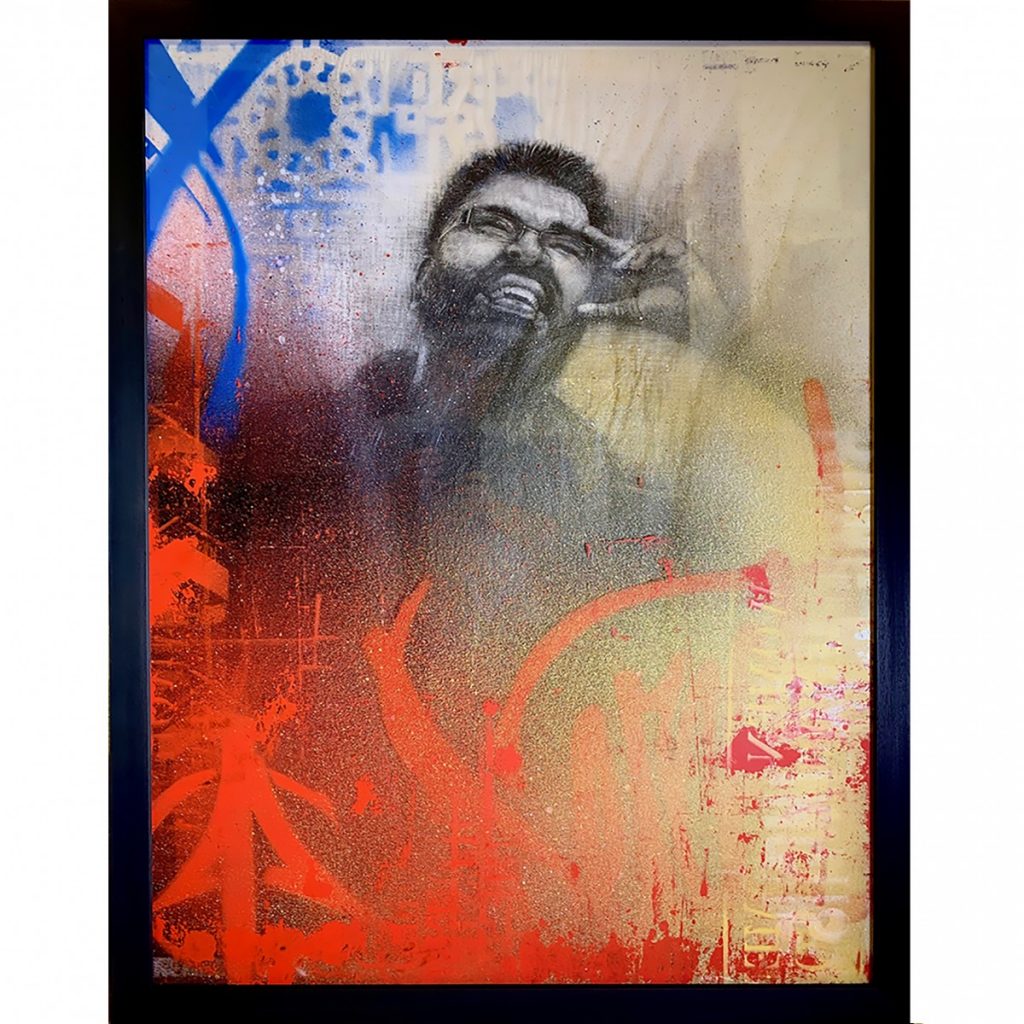

In parallel Mohammed and I had collaborated to make his portrait, again from a discreet photograph that does not allow seeing into the eyes. We both use iPads to plans and create some of our drawings and paintings. I began his portrait portrait by drawing on the ipad before transferring it to a silk screen positive for printing. The prints were made on robust thick fine art Canaletto paper and on tissue paper. On sharing the portraits with Mohammed he was inspired to apply his artistic approach and he led the collaboration to make a (self) portrait by applying spray paint to the tissue prints.

We took it much further by laying acrylic sheets on the image to create layers of colour, shape and texture that could be manipulated individually, much like ‘layers’ in applications such as pro create and photoshop. The sheets with red and blue elements were tested by layering them in different orders and orientations. before the final arrangement was agreed. The collaboration has been dramatic and mutually stimulating, challenging and rewarding.

On completion of the (self) Portrait collaboration Mohammed wanted to make a portrait of another subject to ensure the image would not be an immodest focus only on himself and his image. A gallery of making the portrait is here. This was an additional motivation to make the portrait of Hamza.

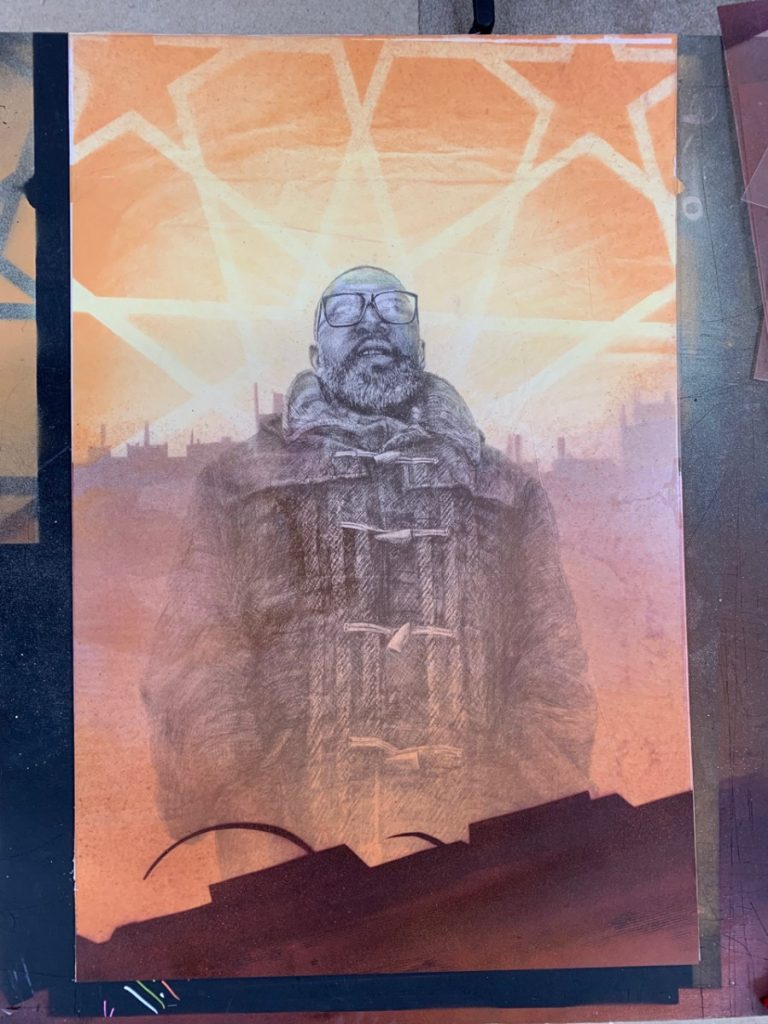

The drawing and subsequent print of Hamza, was made to my satisfaction. Again printed on fine art paper and semi transparent paper. The majority of the image is Hamza’s body wrapped in the warm, thick patterned jacket, with his arms thrust deep into his pockets. His head is drawn with emphasis on his features beyond his eyes, including his close-cropped hair, nose, mouth including glistening gold tooth and white, grey and black beard. The spectacle rims are drawn in dark detail and the reflections only allow a hint of the eye socket and shadows without describing the iris or pupils. Gallery here

Mohammed was inspired by Hamza’s portrait and imported it into the procreate app on his ipad where he created a painted image by painting with colour and shape around and over it. An industrial skyline and modern impressionistic borders were applied. Perhaps this could be printed out on photographic paper at scale in its own right, as well as being preparation for the second collaborative portrait.

We took the same approach to the initial collaboration by adding to the drawn image with painting: a printed portrait on paper mounted on the wall with a sheet of acrylic placed on top for spray painting. A graded orange to yellow was applied with the thought of a graphic landscape to be placed behind the full size portrait.

The next day Aljazeera were in to record an interview with Mohammed in his working studio. He had to tell them not to film Hamza’s image as we had not shared his portrait with him. This encouraged us to contact him to invite him in to see the result.

Hamza came calmly into the studio and surveyed the scene and the range of works. His eyes came to his portrait in progress. A big smile reached across his face followed by a loud laugh of appreciation. After a discussion about the painted portrait the original black and white image was unrolled before the subject.

“I really like this. It looks like me. I like the way you have drawn my jacket. I’ve had it years and people want it from me. It’s not just my face it’s the jacket and the way I stand. The only thing is the angle. My nostrils are a bit to exaggerated. I like how you have done my beard with the different shades.” (I Explained how I use scalpel to scrape to get sharp white hair). “Too much white theses days!”

I responded: ‘if you felt it wasn’t good, or appropriate I would destroy it and all the images leading up to the final portrait. I was definitely open to you feeling like that and would have stopped the process immediately. But as you like it, I want to give it to you. I’ve signed and stamped it, but what should we title it? Hamza, Jason? Nah. Dunno.” What about jacket man? “That’s good, yeah jacket man.”

Hamza reflected: ‘If you had asked me what I would have preferred I would have asked to have a side view, a profile.

I asked: ‘Because you would have want to be portrayed in a thinking thoughtful manner?’

Hamza: ‘Yes that’s right. Thoughtful.’

jT: ’Maybe we should talk about doing another portrait that you determine what would be the best starting image.’ Gallery of the sharing here

After Hamza left with his signed ‘Jacket Man’ portrait rolled and wrapped under his arm, we reviewed the painted image and decided to make further painted additions. A stencil was used to make a pattern from the bottom upwards with the central star of the pattern in the centre. On reflection we agreed that the pattern and centred star was not working well. We took another approach.

A portrait printed on tissue paper was selected rather than the portrait on paper. Additional tissue was added to the top of the portrait to give a better balance. Yellow spray paint was applied around the top of the portrait with orange to the bottom. An industrial skyline was made on separate paper and laid behind the tissue paper. The reframing had worked well for the overall balance of the work. The pattern stencil was placed at the top of the frame, and sprayed with orange, but without the star prominent behind the subject’s head. This allowed the pattern to sit in the skies without drawing attention to the subject’s head and provide a wholeness to the image. Mohammed applied a dark red spray over the orange lower gradation of colour to match the skyline below the tissue paper. He allowed paint to encroach on the body of the portrait and soften the black ink of the portrait. This added to the integrated wholeness of the portrait whereby the subject was not separate, but a part of the totality of the painted and printed portrait.

Finally an acrylic sheet on top of the delicate tracing paper image was spray painted with a dark red and brown paint through a graphic stencil to create a contemporary foreground. Mohammed uses this device on many of his works to create a foreground that situates the subject in a contemporary/industrial/future environment. With the Hamza portrait’s yellow and orange colouration and the over painted orange pattern it could be interpreted as being a Middle Eastern location. By applying a dark red foreground with two ‘cablesque’ curves and tactile marks made with the stencil, a future focused environment to look through was created. A contemporary painting. Gallery here

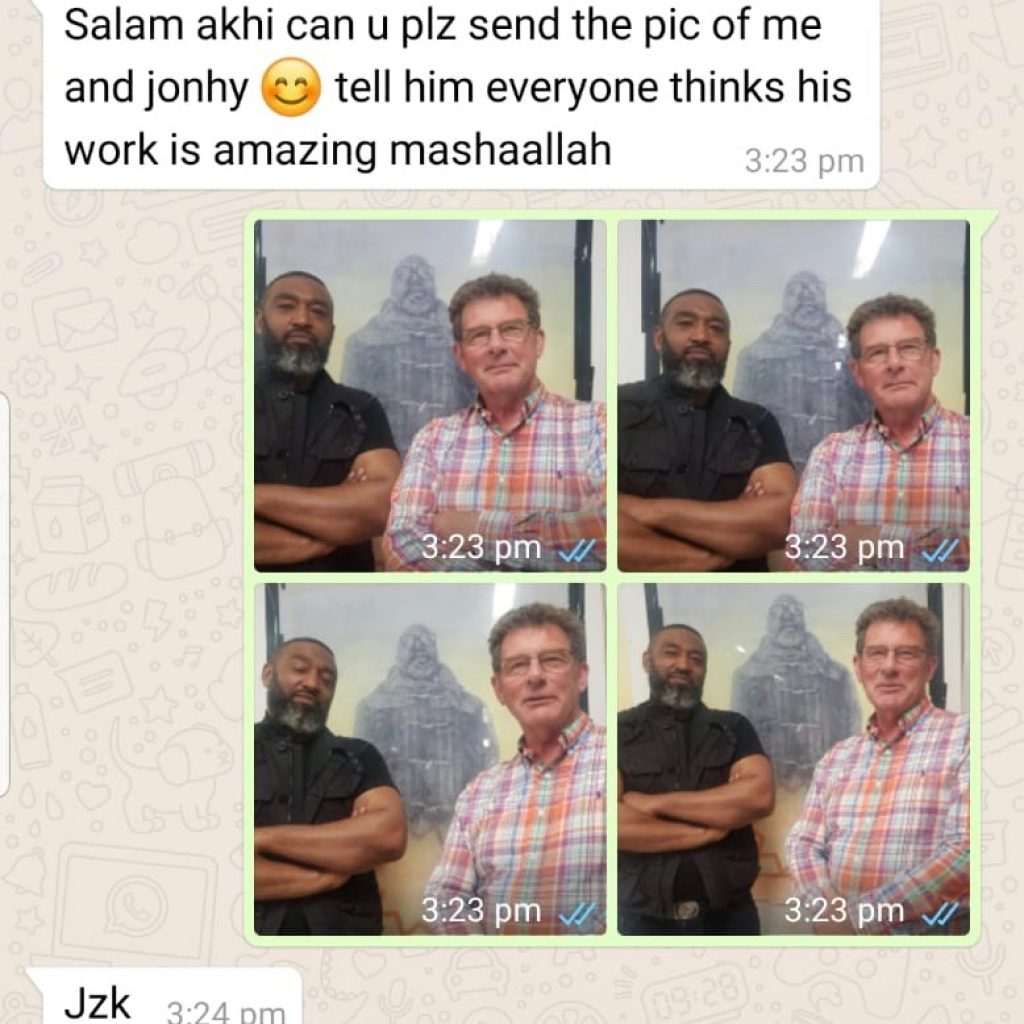

The single finished drawn and painted portrait has been taken to the framers to be framed with the same thick black surround to match the (Self) Portrait of Mohammed. Hamza requested a photo of us and sent the message below.